As a province, the sanctity of Cornwall’s Land's End peninsula is unsurpassed in Britain. So why has its significance been overlooked? I believe the answer lies in its name.

Land's End, Cornwall – England

Nestled precariously on Cornwall’s inhospitable Atlantic coast, the Land's End peninsula is imprinted with thousands of years of myth and legend. Its shores are peppered with romantic coves and secluded beaches while its windswept fields preserve the memory of more dignified times. Today, megalithic monuments, Celtic shrines and ancient tin mines dot the Landscape, recalling the day when pagan princesses, pirates and smugglers roamed the land. The place is special, and has been so for a very, very long time.

The sanctity of Land's End: Lanyon Quoit

In 1998, a team of Russian scientists set out to identify the most likely location for the lost antediluvian civilisation of Atlantis. After considerable analysis they set their sights on Land's End and a stretch of sea 100 miles offshore called the Celtic Shelf. The land, which had been submerged since the last Ice Age, lies just beyond the neighbouring Isles of Scilly. The Russians could be forgiven for believing this was Atlantis; after allPlato quite clearly stated that the fabled city was located just beyond the Pillars of Hercules – or the Straits of Gibraltar, and this is where the Celtic Shelf resides.

Atlantis in Land's End: © BBC

The Russian scientists were likely to have been influenced, or at least romanced, by the legend of Lyonesse; a sunken kingdom with Arthurianconnections believed to have been connected to Land's End in the distant past. The English poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson commemorated the legend in his Arthurian epic, Idylls of the King:

Then rose the King and moved his host by night

And ever pushed Sir Mordred, league by league,

Back to the sunset bound of Lyonesse

A land of old upheaven from the abyss

By fire, to sink into the abyss again;

Where fragments of forgotten peoples dwelt,

And the long mountains ended in a coast

And ever pushed Sir Mordred, league by league,

Back to the sunset bound of Lyonesse

A land of old upheaven from the abyss

By fire, to sink into the abyss again;

Where fragments of forgotten peoples dwelt,

And the long mountains ended in a coast

Here, Tennyson describes Lyonesse as the site of the final battle between Arthur and Mordred. This is not surprising, as traditional mythology associates the Kings of Lyonesse with legendary Arthurian characters, such as Tristan.

Tristan and Iseult (Herbert Draper: 1864 -1920)

As an aside, Tennyson’s work also featured Tintagel, the dramatic and ancient cliff side ruins on Cornwall’s north coast, alleged to have been Arthur’s birth place. Just a couple of miles from Tintagel, in Rock Valley, exists an even more interesting site; a seven ring classical labyrinth carved on a rocky outcrop. The symbol of the labyrinth was prevalent across the ancient world and is thought to represent spiritual pursuits and otherworldly realms. The design dates back millennia, and some argue, all the way back to the time of Atlantis.

The Arthurian Tintagel...

...and the nearby Labyrinth at Rock Valley, Cornwall

However, most believe that the association of Lyonesse with Atlantis is merely a folk memory of the flooding of the region around the Scilly Isles. But does that confirm or invalidate the historical context of the myth? Take for instance the Trevelyan family of Cornwall, who derive their coat of arms from the story of when Lyonesse sank beneath the waves and the sole survivor - a man named Trevelyan - escaped on a white horse. Based on the legend, the family adopted a shield with a horse rising above the waves. Regardless of its authenticity the memory of a cataclysmic flood and a surviving flood hero appears to have been retained in the folklore of the peninsula and its people, like it has in so many ancient lands.

The Trevelyan Family Crest: A horse running from a flood

Not far from where Lyonesse is said to have flourished - and ultimately perished, Saint Michael's Mount sits stoically on a jagged grey hill across the bay from Penzance. At low tide the majestic castle is joined by a natural causeway with Marazion, a town believed to be the oldest in Cornwall, and as we shall see, some would argue the oldest in all of Western Europe.

Causeway leading from Marazion to Saint Michael's Mount at low tide

The Cornish name for Saint Michael's Mount means "the grey rock in the wood". A forest once populated Mount Bay and the dramatic outcrop of grey granite could be seen rising above the tree line.

As with many sites revered by ancient pilgrims and modern-day spiritualists, an apparition or religious vision occurred at Saint Michael's Mount. Legend tells us that the Archangel Saint Michael appeared in 495 A.D. and a church was promptly erected in his honour. A few centuries later, a Celtic monastery was established and presided over by Benedictine monks.

A local tale popular with tourists recounts how a giant named Cormoran terrorized the Mount before being tricked and slain by a farmer’s son named Jack. The giant’s heart was removed, preserved and incorporated into the cobbled stone pilgrim’s path leading to the Mount. The stone immortalizes the memory of Cornish man’s victory over evil, and the beast with the ‘heart of stone’.

The giant’s heart on the pilgrim’s path leading up the Mount

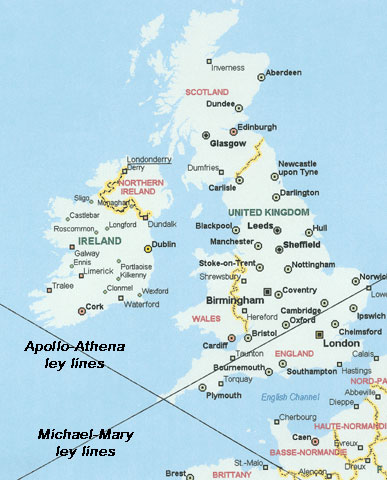

Any review of the legends of Saint Michael's Mount would be incomplete without mention of the Saint Michael's ley line that runs northeasterly from Mount Bay across the country for several hundred miles, intersecting ancient edifices dedicated to Saint Michael in its path. Real or imagined, this granddaddy of ley lines runs through sacred sites such as St Michael's Church Brentor, St Michael's Church Burrowbridge, St Michael's Church Othery, St Michael's Church, Glastonbury Tor, and Stoke St Michael before coming to an apparent end in Bury Saint Edmunds, Norfolk.

Research by authors Hamish Miller and Paul Broadhurst has identified another ley line that intersects the Saint Michael line – at Saint Michael's Mount. The line starts in Ireland at the monastery of Skellig Michael before connecting to Saint Michael's Mount in England, France's Mont Saint Michel, and then onto a variety of sacred sites, such as Sacra di San Michele, Assisi, Delphi, Athens, Rhodes and ultimately Mount Carmel in Israel. Whether one attributes these alignments to serendipity or conscious design, they certainly add to what is undoubtedly a magical legend.

Land's End – the intersection of the Michael and Apollo Ley Lines

© Owen Waters

© Owen Waters

A special relationship exists between Saint Michael's Mount in England, and Mont Saint-Michel in France. The sites are effectively mirror images of each other, i.e. name, setting, history, etc. and their visual similarities are striking. Curiously, even the most callused visitor can sense the extraordinary energy they produce.

Saint Michael's Mount - England

Mont Saint Michel - France

The two centres of worship also share the same apparition; Saint Michael is said to have appeared in a vision at the French Mont St Michel in 715 A.D., and at the Cornish St Michael's Mount, as previously noted, in 495 A.D.

The list of similarities between the two lands just goes on. Another interesting, inverse relationship between Cornwall and France is their flags. The Cornish flag is a white cross on a black background while the former Breton (Brittany) flag is a mirror of the Cornish.

The Cornish Flag and the French Breton Flag – mirror images

The Cornish flag is called the banner of Saint Piran; the patron saint of tin-miners. Cornwall, as we shall discuss in some detail, was a major tin mining centre in the ancient world and Saint Piran is alleged to have adopted the flag’s color and design after witnessing the white tin in the black coals during his discovery of tin. Oddly, both flags are known by the same name; Kroaz Du, meaning Black Cross. The Black Cross is said to have been the flag used by the first Crusaders, and symbolizes the light of truth shining through the darkness of evil.

The Cornish Coat of Arms represents another Crusader reference; its shield depicts 15 gold coins (bezants) in the shape of a triangle and includes the motto One and All. The story goes that the Saracens had captured the Duke of Cornwall and were holding him ransom in exchange for 15 gold coins. In order to save their hero, Cornish people from all walks of life rallied together and raised the necessary money to free the Duke, hence the motto, One and All.

Not surprisingly, the Cornish Coat of Arms is enclosed by a frame of waves – much like the county itself is enclosed by water, echoing the memory of Lyonesse. Above the shield is a Chough, a member of the Crow family of birds, and a local legend in Cornwall. The Chough was once quite common on the cliffs of Cornwall, but was extinct for 50 years until conservationists re-established it through breeding in captivity near Land's End. Cornwall without the Chough is similar to the Tower of London without the Raven, and its return, albeit through controlled means, is viewed as highly auspicious. Standing on either side of the Chough are a tin miner and fisherman, symbolizing Cornwall’s two most important trades, historically.

Cornwall’s Coat of Arms and the Cornish Chough

There are still further similarities between Cornwall and Breton, such as their flood mythology. Like the legend of Lyonesse, Breton has its own version of a sunken kingdom in the tale of the Cité d'Ys, which was submerged as a result of its wantonness. As in the story of Lyonesse, the Breton flood myth ends with a sole survivor - King Gradlon – who manages to escape on a horse.

There are also similarities between the Cornish and Breton languages, no doubt stemming from a common Celtic Past. Clearly, the parallels reinforce the belief that in ancient times the two lands where connected in special ways, now largely forgotten.

The ancient village of Marazion connects Saint Michael's Mount to the Land's End Peninsula via a tidal walkway. The place is special in Cornish traditions; John Wesley preached there and the first Quaker meeting house in Cornwall was established there over 300 years ago. However its true place in history goes back much further, still.

Marazion, Land's End Peninsula

The name ‘Marazion’ is an amalgamation of two adjacent villages that have merged into one; Market Jew (Marghas Yow, or ‘Thursday Market’) and Marazion (or Marghas – or ‘Little Market’). Both names are Cornish, and local historians are quick to point out that neither implies a connection with Jews or Zion. Still others translate Marazion as ‘Zion by the Sea’, and as we shall see, this is not as farfetched as it first appears.

Marazion may well be the oldest town in England and possibly all of Western Europe. This is due to the belief of some historians that Marazion is the Mictis of the historian Timaeus and the Ictis of Diodorus Siculus; the author of each work studied the lost texts of Pytheas, an ancient Greek geographer who visited Britain in the 4th century BC.

Marazion may well be the oldest town in England and possibly all of Western Europe. This is due to the belief of some historians that Marazion is the Mictis of the historian Timaeus and the Ictis of Diodorus Siculus; the author of each work studied the lost texts of Pytheas, an ancient Greek geographer who visited Britain in the 4th century BC.

Certainly the stone carvings in the cemetery of All Saints church (formerly Saint Hilary’s, which burnt in a fire in 1853) confirm an ancient origin, as several date from the 4th century and one even pays tribute to Constantine the Great. Another stone is inscribed with ‘NOTI NOTI’, which has been translated as the mark of Notus, however accompanying the inscription are symbols whose meaning remains a mystery.

Inscribed stones of Saint Hilary: unidentified characters on the right

© Chris Bond Photo and Blight 1856 sketches

© Chris Bond Photo and Blight 1856 sketches

There is ample evidence of the presence of Jewish communities in Land's End in modern times. Just down the road from Land's End point, in Sennen Cove, the 1876 Round House contains a Star of David carved in a roof beam. The house was constructed to allow fishermen to dry and mend their nets before trips.

Star of David in Land's End fisherman’s house (Sennen Cove)

Still one must ask what proof exists to confirm a Jewish occupation in Cornwall in ancient times. Cornwall’s Red Book of the Exchequer, circa 1198, contains a clause referring to every "man or woman, Christian or Jew." However to find earlier references we must turn our attention to more speculative accounts of fabled biblical characters and England’s most enduring legends – those of Christ on its shores.

Cornwall has been coveted since ancient times for its abundant tin mines. The Phoenicians traded cloth for it, and merchants of all backgrounds sailed far and wide to barter their wares for the rare and valuable commodity. Research by Adam Rutherford, author of 1939’s Anglo-Saxon Israel or Israel-Britain reveals that Cornish tin:

"…is mentioned by such classical writers as Herodotus, Homer, Pytheas and Polybius, whilst Diodorus Siculus gives the details of the trade route."

Researchers and historians have noted that Christ’s uncle, Joseph of Arimathea, was a wealthy Jewish tin trader who made regular trips to Britain. Legend suggests that on at least one occasion he was accompanied by his nephew, Christ.

The tin trader: Joseph of Arimathea by Pietro Perugino (a detail from a larger work)

Joseph is best known for offering his tomb to accommodate the body of the crucified Christ, an act that fulfilled Isaiah's prediction that the grave of the Messiah would be provided by a wealthy man:

“He was assigned a grave with the wicked, and with the rich in his death.”

Joseph is less known for his role as a tin merchant, and this should come as no surprise as there are few detailed accounts of his life. Nevertheless, there are countless legends of Joseph and Christ in England, a handful of which we shall review now.

The 19th century children’s lullaby recounts the legend plainly:

"Joseph was a tin merchant, a tin merchant, a tin merchant. Joseph was a tin merchant and the miners loved him well."

Similarly, in the 19th century, the residents of the West Country tin mining village of Priddy had an equally simple expression:

"As sure as our Lord was in Priddy."

The nine megalithic barrows of Priddy

Fortunately there are more references than mere nursery rhymes. Eusebius, an ecclesiastical historian who was regarded as the Father of Church history, wrote three hundred years before Augustine came to Britain that:

“The Apostles passed beyond the ocean to the Isles called the Brittanic Isles”.

Several early historical accounts write of Joseph’s travels and one in particular, from the ancient Glastonbury Chronicle, records an interesting meeting between Joseph and the British King Arviragus:

“Joseph then counselled the King to believe in Christ: King Arviragus refused this, nor did he believe in Him. Arviragus the King gave him twice six hides at Glastonia. Joseph left the rights with those companions in the XXXI year after the Passion of Christ. These men, with praises built a church of wattles.”

Another West Country legend builds on the Glastonbury theme:

“Joseph of Arimathaea, a rich man and disciple of Jesus, fled the Holy Land to escape the persecution of the followers of Christ. Journeying to Britain in hopes of spreading the faith there, he arrived in Glastonbury weary and discouraged, for his teaching had had little effect. He prayed for a miracle to convince the unbelievers, and when he thrust his staff into the earth, it burst forth into leaf and sweetly-scented blossoms.”

The original Glastonbury Thorn, which died in 1991

Joseph’s association with Glastonbury – a town long believed to be the true Arthurian Avalon, appears to have been the impetus for his association with the Holy Grail. As the 13th century approached the Burgundian poet Robert de Boron wrote the first account of Joseph’s life – the aptly named Joseph d'Arimathe, which featured the Holy Grail as the chalice used at the Last Supper. The cup was given to Joseph by his superior Pontius Pilate, who as another legend recounts, hailed form Fortingall Scotland – a strange village in the exact centre of Scotland with the oldest tree in Europe and a number of ancient stone circles and carved stones with cup marks.

Fortingall – the alleged home of Joseph’s superior – Pontius Pilate

Boron tells us that Joseph used the cup to catch the blood of Christ as he was dying on the cross and that later, Joseph’s followers took the chalice – the Holy Grail – to Britain. From this point onward, Joseph, Christ and the Holy Grail were inseparable in literature, and the story was regarded as fact in countless new age accounts.

What’s intriguing and certainly worth mentioning is the similarity in the Cornish mythology of Arthur and Christ. In fact, one could be forgiven for believing they were the same person. References to each occur over and over again in the southwest of England, and in his book Arthurian Britain, Geoffrey Ashe attributes nearly fifty Cornish sites to Arthur, alone. The similarities between the two icons are worthy of a review:

- Each has a mystical legend in Cornwall

- Each had strong association with the Holy Grail

- Each had 12 initiates (Apostles | Knights of the Round Table)

- Each was mentored by a wise man (John the Baptist | Merlin)

- Each partnered with a mystical woman (Mary Magdalene | Guinevere)

- Each was born under auspicious circumstances and died with mystical associations and a prophecy to return from the dead in our hour of need.

Once again, the similarities are interesting, and would appear to represent an archetype of some sort of Grail Savior – a theme of considerable significance in Cornwall.

We return to Joseph, not in the context of the Grail, but rather tin. Joseph was regarded as a trade hero by metal workers across England and at least one researcher, the Rev Lionel Smithett Lewis, author of 1953’s St Joseph Of Arimathea At Glastonbury, placed his entry into Britain at Marizion. Lewis wrote:

"We workers in metal are a very old fraternity, and like other handicrafts we have our traditions amongst us. One of these... is that Joseph of Arimathea, the rich man of the Gospels, made his money in the tin trade with Cornwall. We have also a story that he made voyages to Cornwallin his own ships and that on one occasion he brought with him the Child Christ and His Mother and landed them at St Michael's Mount (my italics)."

On December 22, 2007, the Daily Express newspaper in the UK ran an article entitled ‘Our Mythical Christmas’ that recounted the now familiar tale. The article placed the specific landing spot of Christ in Brittan at Looe Island, just up the coast from Land's End. Curiously, folklore at Looe associated with the megalithic monument called the Giant's Hedge indicates that a centenarian of Looe is on record as having said:

"The piskies of Cornwall heard that a little boy and his uncle had landed at Looe Island, and they were so anxious to protect them, that they went to the giants, and got them to build a hedge."

The Giants Hedge – Looe © Hamhead

However, the most popular account of Christ in England belongs to William Blake, whose epic poem Jerusalem (subtitled The Emanation of the Giant Albion) is widely believed to reference the presence of Christ in England. Blake, a member of The Royal Academy, began the poem in 1804 and finished it some 16 years later – complete with 100 illustrations.

William Blake by Thomas Phillips, 1807

The poem contains an obtuse reference to ‘dark Satanic mills’. The expression is ambiguous to our 21st century mind, although its meaning has been the subject of heated debate down through the years. Most believe the phrase references tin mines – a symbol of the evil and ruthlessindustrial revolution according to Blake. In Jerusalem, Blake wrote the now seminal text:

“And did those feet in ancient time

Walk upon England's mountains green?

And was the holy Lamb of God

On England's pleasant pastures seen?

And did the Countenance Divine

Shine forth upon our clouded hills?

And was Jerusalem builded here

Among these dark Satanic mills?”

Walk upon England's mountains green?

And was the holy Lamb of God

On England's pleasant pastures seen?

And did the Countenance Divine

Shine forth upon our clouded hills?

And was Jerusalem builded here

Among these dark Satanic mills?”

Tin mines – Land's End

Few recall that Blake’s popular poem was written as a preface to another more important piece, namely Blake’s larger-than-life work, Milton. The hero of the story, John Milton, returns from heaven and encourages Blake to develop his relationship with dead writers. The poem is apocalyptic and deals with the union of the dead and the living, the male and the female, and varying forms of reality.

Milton – the hero of Blake’s epic poem of the same name

So was Blake merely preserving the memory of when Joseph of Arimathea travelled to Britain with his nephew, Christ – or does it allude to something more – something different? Again, the debate on what exactly was meant by ‘dark Satanic mills’ has ranged from megalithic sites, which Blake regarded as satanic, to the coming of the industrial revolution – which he found even more distasteful, to the perceived evils of the Church of England and even the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge. The megalithic association with ‘dark Satanic mills’ is interesting for Cornwall, and Land's End in particular, possess more than its share of tin mines – the precursor to the industrial revolution, as well as stone circles, standing stones, dolmen and an unusual underground monument indigenous to the peninsula, called Fogou’s.

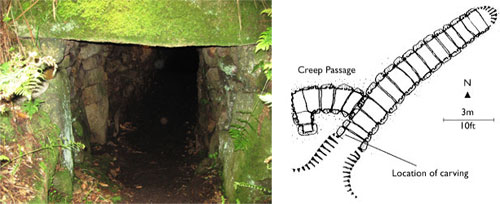

Standing at the entrance to the Carn Euny Fogou

Fogou’s are a peculiar type of ancient monument, unique to Land's End. Its name derives from fogo and fócw, meaning ‘Cave’ in Cornish and Celtic languages, respectively. Fogou’s are thought to date from the late Iron Age – circa 500 BC. Their primary feature is a curved roof passage leading to an underground hollow, where an adjoining chamber is reached through what is known as a “creep” passage. Typically the main passage – not the entrance – is astronomically aligned.

The layout of a typical Fogou: Pendeen Fogou

Not surprisingly, the archeological jury is undecided as to the function of the Fogou. Practical theories suggest they were used for food storage – particularly the drying of meat, and / or provided shelter from the harsh winter snow and rain, not dissimilar to how Tacitus, the Roman senator and historian form the end of the 1st century, describes caves built by Germans for the same purpose. This theory is strengthened by the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus, who observed that tribes in Iron Age Britain built 'underground repositories' to store their grain. However, Fogou’s are extremely damp and constructed with elaborate lintels too narrow for normal human activity, leading many to conclude that their function was more ritualistic than domestic.

Halliggye Fogou entrance

Halliggye Fogou main chamber

The prevailing consensus is that Fogou’s were religious centres built by chieftains for shamanic rituals and initiations. To this day, those who enter Fogou’s experience otherworldly images, particularly women, and some Forou’s are used by New Age communities as re-birthing ritual centers, such as the Boliegh Fogou.

The Boleigh Fogou was first excavated in 1957 by Dr E. B. Ford. Not only was Ford able to uncover pottery dating parts of the structure to the late Iron Age, La Tène B Period (circa 450 BC), but he noticed something quite peculiar on the left side of the Fogou entrance. In the words of the former site owner, Jo May:

“He arranged for the boulder to be photographed with infrared film and the resulting photograph revealed a male figure, apparently full-faced, with long hair around the head, the left side of the face being flecked away. The right arm, raised from the elbow, supports a spear; the left is held horizontally to the elbow, the forearm being lifted vertically, the hand grasping a lozenge shaped object possibly the head of a serpent, one of the coils of which being dimly suggested round the wrist. Although related to similar figures in Brittany, the carving was unique in Britain.”

Boleigh Fogou – entrance and internal schematic

The next, serious excavation of the Boleigh Fogou came in 1995 from the British Television Series Time Team, whose work revealed a previously undiscovered house enclosed by an oval wall with over sixty pieces of pottery dating form the early Iron Age. Refreshingly, Time Team concluded:

“There was a lot more to these structures than could be explained by conventional archaeology” and that “the Fogou was designed for religious use by the settlement.”

Left: Time Team aerial reconstruction

Right: May’s interpretation of their findings (Courtesy Jo May)

Right: May’s interpretation of their findings (Courtesy Jo May)

Aileen Fox points out in his 1973 South-West England 3500 BC - AD 600 that most Fogou’s were constructed facing the prevailing winds. Others have noted that their orientations favor the rising and setting midwinter sun. Cheryl Straffon argues in her book, Pagan Cornwall, that Fogou’s were ritualistic centres built in honor of the Mother Goddess;

“Who by now (Iron Age) may have been identified primarily as an Earth Goddess.”

Earth energy proponent Paul Devereux points out in his book, Power Places that the radiation levels in Cornwall are abnormally high in general and twice as powerful in underground chambers, such as Fogou’s. Many believe this fact offers an explanation for the large number of hallucinogenic experiences that occur in these structures.

Fogou’s represent a unique aspect of Land's End’s prehistory, and are at risk of being consumed into working farms and private estates. At Pendeen Vau, the ancient Fogou has been incorporated into a working farm / Bed and Breakfast. Coincidently, legend states that the Pendeen Vau chambers reach for many miles under the Atlantic Ocean. Julian Cope comments on this in his excellent book, The Modern Antiquarian:

“Even scholars believed this to be true as late as 1584, when Norden the Antiquarian, in his Survey of Cornwall, wrote the tide flows into the cave, at high water, very far under the earth.”

The Fogou of Peenden Vau

Generally speaking, Land's End’s Fogous are unique in Britain, yet bear a striking resemblance to the French Souterrains (meaning under ground) of Brittany. Again, this is not surprising as we have already touched upon many of the similarities between these two lands. Celts from Brittany are known to have sailed to Land's End and landed at Lamorna Cove – not far from the Boleigh Fogou.

Lamorna Cove – where French Celts from Brittany once landed

Here, dozens of enigmatic megalithic monuments haunt the landscape – as they do in France at the more famous megalithic centre known asCarnac. Sadly, the spectacular megalithic sites of Land's End deserve more mention than can be afforded here, however we will indulge in one particular site just a bit further.

Boskawen-Un Stone Circle

Chu Quoit

Carn Euny Fogou

Carn Gluze

In the middle of a desolate field more frequented by mist and fog than sun sits Land's End’s most celebrated megalithic site, Mên an Tol; the crick stone, so named for its ability to help cure back aches. Mên an Tol is one of several holed stones on the peninsula and both folklore and archaeology suggest a ritualistic function.  Mên an Tol – tin mine in the distance Children with rickets were cured when passed 3 or 9 times through the hole against the sun. Adding to the myth, in more recent times an incident was reported when the Pisky guardian of the site was thought to have swapped an innocent human child for one of his own. The child’s despondent parents were required to pass the pisky child through the holed stone in order to reclaim their human child.  Mên an Tol: The hole children with rickets were passed through 3 or 9 times Mên an Tol sits along the Tinners Way, a 12 mile pathway that connects ancient sites across the West Penwith moors from St Ives to St Just. In a famous case from 1977, a couple lodged a complaint with local authorities after being attacked by circling balls of light while walking on the pathway. The Tinners Way eventually meanders along the outskirts of Zennor, an ancient village known for its stone rows, witch’s rock, quoit and legends of mermaids.  The hamlet of Zennor and St. Senara’s church; home of the mermaid bench The legend of the Zennor mermaid is preserved in a 600 year old carving of a mermaid on the side of a bench in the Zennor church.  The Zennor mermaid bench The legend recalls the day when a mermaid lured a local man out to sea – never to be heard from again. The young man, named Matthew Trewhella, was admired by the mermaid for his exquisite voice and splendid singing in the local church choir. Eventually the mermaid overcame her inhibitions and started to visit Trewhella more frequently, remaining as long as possible before returning to the sea. Ultimately, the young man became equally enchanted with the mermaid and one night followed her into her watery realm, never to be heard from again. The entire locale is captivating and supports the legend in peculiar ways; nearby is a field with the ancient place name of The Green Man, and a little further along the coast is the village of Morvagh, which recalls the name Morverch, meaning mermaids or alternatively, sea grave. Curiously, the tale of the mermaid is recalled across the peninsula at the cove of Porthgwarra. Here a natural cave structure forms a benevolent looking guardian face that looks out over the natural harbour below.  Porthgwarra cove guardian  View of cove from above the ‘head’ The legend of Porthwarra parallels that of the mermaid at Zennor but for one intriguing difference; here the roles are reversed. This time, legend recalls a young man who lured his lover into his watery realm. The story recounts the tale of a young Cornish sailor who fell in love with the local farmer’s daughter. The couple vowed to wait for each other while the young man was at sea for several months, but he never returned, and after three years time was presumed dead. Then one night the young man appeared at his lover’s window, beckoning her to follow him to the cove where his boat was waiting; they would be together once more. His lover obliged, and neither was heard from again. Just what, if anything, are these curious legends of lovers lured into mystical watery realms meant to convey? The first account of mermaids appeared in Assyria around 1000 BC; 3000 years later they remain alive and well in Cornwall. Do they speak of the same memory?  A Mermaid by John William Waterhouse While the mermaid is a popular image in old church frescoes across Cornwall, Saint Senara church in Zennor, Land's End, is in fact the only example of a mermaid carving. However, other carvings in Land's End eco a similar memory of fairytales and legends, and are worthy of mention. At Saint Levan Church a number of curious bench-end carvings echo those of the mermaid in Zennor. Here serpents, griffins and other-worldly creatures commemorate the church’s pagan past.  Saint Levan’s Celtic church screen  Celtic bench ends In the church grounds the pagan origins of the parish are recalled in a curious boulder called Saint Levan’s Stone. Legend purports that the rock was split in half by the staff of the Saint himself, who uttered the peculiar prophecy: When with panniers astride, A pack horse can ride, Through Saint Levan’s Stone, The World will be done. Like many pagan shrines in Land's End, Saint Levan’s stone is associated with fertility rites.  Saint Levan’s church  The split boulder at Saint Levan’s church Saint Levan’s and Saint Senara are but two of many churches in Land's End with unique esoteric history. Another is Saint Buryan, which boasts two Celtic crosses and an abundance of chalice symbolism:  Saint Buryan Chalice Carvings Saint Just-in-Penwith is the nearest town to Land's End and maintains a 14th century church built over a far earlier place of worship. A Celtic cross adorns the cemetery and inside the church are a number of peculiar artifacts, including an original wall mural of a figure surrounded by unusual objects ,such as scales, an anvil and hammer, a horn, a mermaid, a rake, a ladder and a boat bearing a fish, amongst others. West Penwith Resources informs us of a curious mystery surrounding the painting: “Beneath this painting the workmen found that some of the wall had been removed, and a rough recess formed, 2 ft. 7 in. by 1 ft. 2 in., and 2 ft. deep. It contained a skull and other human bones… which appear to have been hastily deposited, and then walled up.” Just what - and whom - was concealed beneath the painting remains a mystery. And like so many aspects of Land's End, what little we know suggests there is much more we have yet to learn.  Celtic Cross in front of St. Just Church  Ancient fresco inside the church Cornwall boasts an impressive assortment of local Saints and many early Christian shrines on the Land's End peninsula recall their glory. It’s worth noting that these Saints are not in fact canonized, but rather represent an assortment of local druids and missionaries from Wales and Ireland who were revered within the community for their perceived holiness and ability to teach. Of all the shrines dedicated to them, none is as widespread or arguably as evocative as the holy wells of Land's End. Over two dozen holy wells exist in the immediate vicinity of the Land's End summit, the most famous being the Holy Well at Madron. Here the ancient ruined chapel continues to draw visitors, mostly the physically disabled who are and hoping to reproduce the fortune of John Trelill, a 17th century man who was handicapped for 16 years yet cured of his affliction after bathing in the well’s holy waters. Nearby, pilgrims underscore their prayers by leaving a cloth in a sacred spirit tree.  Mardon Well and spirit tree Much of what makes Cornwall special, and Land's End in particular, is simply its unique Cornish heritage. Sadly, the ancient Cornish language is no longer spoken and many believe it died when Land's End resident Dorothy Pentreath passed away in 1777. Pentreath was regarded as the last Cornish speaking resident, and with her passing, symbolically if not literally, an end of an era may truly have passed.  Grave of Dorothy Pentreath Despite the passing of Pentreath, Cornwall’s old customs are preserved in surprising ways. In Helston - just up the southern coast from Land's End - an annual ceremony marks the passing of winter and the arrival of summer. The Furry Dance, or Flora dance as it is called locally, takes place on May 8th – the feast day of Saint Michael. Amongst the day’s many festivities is a ritual called Hal en Tow – the oldest portion of the entirely pre-Christian celebration. The ritual includes the singing of a song about Robin Hood, Saint George and the coming of summer. Interestingly, in old English an alternative spelling of Robin was Hob, which in medieval times meant spirit of the underworld, prompting one to speculate if Robin Hood was in fact a Pisky?  Helston May Day celebration Similarly in Padstow, just up the northern coast from Land's End, an annual May Day celebration is held called the 'Obby Oss’ festival. The ritual celebrates the Celtic festival of Beltane and commences at midnight and lasts the entire next day.  The Obby Oss festival – Padstow Today, Land's End remains a popular tourist destination and a paradise for hikers, cyclists and enthusiasts keen to undertake the well traveled 874 mile journey from John O’Groats, Scotland to Land's End, the southern most tip of the island. Disappointedly, Land's End village has been horribly exploited in recent years, having been reduced to a second rate children’s amusement park.  Land's End summit, Cornwall Only the nearby Minic Theatre – a significant tourist attraction in its own right, remains in keeping with the grandeur of the landscape and its legends.  The Minic Theatre – Land's End I mentioned from the start that Land's End may not be fully appreciated due to its name. What I meant was here is a land so steeped in myth and legend that its narrow shores are the archetypes for both Atlantis and Christ in England, not to mention legends and apparitions of Saint Michael, mermaids, pirates, pixies, pagans and megalithic man. I believe that the whole of Cornwall is special, albeit under-appreciated, and Land's End in particular. Thus, all things considered, I believe a more fitting name might be Land's Beginning. I suspect you agree.  Land's Beginning at sunset |

No comments:

Post a Comment