Mitra

¿Antecedente Del Cristianismo O Culto Plagiado?

Alrededor de 3.500 años antes de Cristo aparecen en los Vedas, libro sagrado de la India, las primeras referencias al dios Mitra. Se le nombra como dios unido a Varuna. Ambos formaban una dualidad inseparable; Mitra era el dios del amanecer, de la luz y del sol; Varuna es el dios del crepúsculo y de la noche. Ambos, luz y oscuridad se encargaban del buen funcionamiento de la bóveda celestial.Por influencia de los arios hindúes que se trasladaron hacia el actual Irán y Turquía, ya en el año 1.400 antes de Cristo, se le nombra como dios garante de un tratado entre los Hititas y el Reino de Mitanni, situado en el actual Kurdistán, a caballo entre Turquía e Irak.

Alrededor del año 1.000 antes de Cristo, nace en Bakctriana, ciudad de Persia— actual Irán— un hombre llamado Zaratustra. Este hombre es considerado por muchos historiadores como el primer ser humano que cambió verdaderamente la Historia y la concepción del mundo y de la persona.

Zaratustra recibió una “Revelación”, proclamando al verdadero dios, creador del Universo, al que llamó Ahura Mazda que significa “Señor Sabio”. En oposición a él, estaba Angra Mainyu que significa “Demonio de la Mentira”. Ni qué decir tiene que ambos personificaban el Bien y el Mal. Ambos luchaban por imponerse sobre la Creación y sobre los hombres.

El Mandeísmo, nombre dado a esta revelación, fue la primera gran religión que tuvo un libro sagrado, el Avesta, que significa “La Palabra”, y su antigüedad es mayor que la Biblia, la cual tomó de este libro algunos de sus pasajes más conocidos.

Historiadores y filósofos confirman que el Mazdeísmo fue el precursor de las grandes religiones monoteístas basadas en libros sagrados, como el Judaísmo, el Cristianismo y el Islamismo, las cuales beben en sus fuentes originales, los dogmas y enseñanzas de Zaratustra.

Desgraciadamente, sólo se conserva un tercio del libro original escrito por Zaratustra al dictado de Ahura Mazda, según le iba siendo revelado. Lo más extraordinario, es que Zaratustra tuvo doce discípulos, la tradición persa le otorga la autoría de cientos de milagros y curaciones, incluso la resurrección de varios cadáveres.

En la religión mazdeísta ya se habla de un diluvio universal, de un arca en la que se salvaron una pareja de animales de cada especie y una familia. Se entroniza una Santísima Trinidad compuesta por los dioses Ahura Mazda, Mitra y la diosa Anahita, esposa de Ahura Mazda y madre de Mitra.

El Mazdeísmo habla de la primera pareja humana, de Paraíso, del Cielo y del Infierno, del juicio tras la muerte, de la resurrección de los muertos y del juicio final, tras la victoria sobre Angra Mainyu, ayudado por sus demonios, mientras Ahura Mazda y Mitra serán ayudados por los ángeles y arcángeles.

También anuncia el Avesta, la aparición en La Tierra de un Salvador, un Redentor de la Humanidad, que vendrá a enseñar a los hombres su misión en la vida y a vencer al mal.

Este redentor es Mitra, hijo de Ahura Mazda. Según el Avesta, Mitra nació en una gruta el día 25 de diciembre. Una luz resplandeciente situada sobre la gruta despertó a unos pastores que fueron a adorarle. Unos magos, enterados por las estrellas de su nacimiento, fueron a obsequiarle ofrendas. En la gruta, un buey y una mula ayudaban a calentar al niño dios. Los mazdeístas creían que Zaratustra era una encarnación del dios Mitra, que había venido a la Tierra para salvar a la Humanidad.

Mitra, tras su nacimiento, ayunó en el desierto durante cuarenta días y sufrió una “pasión” que se celebraba en la semana del 23 de marzo, con la llegada de la Primavera. Curiosamente es la fecha aproximada en que se celebra la Pasión de Jesucristo.

Durante dicha pasión, Mitra se veía obligado a matar a un toro, de cuya sangre brotaba toda la Creación.

Plutarco, habla de los misterios de Mitra en el año 87 antes de Cristo, ya que esta religión, la Mitraica, se extendió por todo el Imperio Romano llevada por las legiones que la adoptaron en masa cuando llegaron a Asia Menor. Incluso el emperador Trajano la protegió y declaró el domingo día del sol dedicado a Mitra como día festivo en todo el imperio, más tarde lo adoptó también el cristianismo como día del Señor.

La religión Mitraica tenía en su liturgia el bautismo con agua para ingresar en la misma y la confirmación posterior. En la entrada de los mitreos o templos, estaba situada una pila con agua bendecida por los sacerdotes en la cual se mojaba la mano y luego la frente para entrar purificados. Se realizaba una ceremonia o ágape, en el cual se bendecían el pan y el vino o agua, y se repartía entre los asistentes como si fuera la carne y sangre de Mitra de forma simbólica. Se cantaban himnos en honor a Mitra.

El clero estaba estructurado entre Padres, o sacerdotes comunes, Amtistides u obispos y Pontífices. Sobre todos ellos gobernaba el Padre de los Padres, título equivalente al de Papa.

Las fechas más señaladas en el calendario sagrado de Mitra eran: el 25 de diciembre, día del nacimiento del dios; el 6 de enero, día de la adoración de los magos; el 24 de marzo, semana de pasión de Mitra; el 6 de mayo, revelación del Avesta a Zaratustra; el 16 de mayo, comienzo del ayuno de Mitra en el desierto; el 24 de junio, Mitra asciende a los cielos y es proclamado segunda persona de la trinidad; el 16 de agosto, Mitra es nombrado por Ahura Mazda intermediario entre él y los hombres y se le otorga todo el poder sobre la Tierra y sus moradores.

La religión de Mitra era una religión mistérica, es decir, que guardaba algunas ceremonias en secreto sólo para unos pocos iniciados. Los creyentes en Mitra no eran admitidos de inmediato a todos los secretos de la liturgia ni se le explicaban todas las doctrinas y dogmas. Existían una serie de grados, a través de los cuales iban ascendiendo los fieles según su preparación y la piedad de su vida demostrada ante los sacerdotes y compañeros de culto.

La religión de Mitra se extendió por todo el Imperio Romano. El Cristianismo y el Mitraismo convivieron hasta la llegada al poder de Constantino el Grande, el cual, creyente de Mitra, no dudó en aprovechar la ocasión para fusionar ambas doctrinas. El Cristianismo adoptó la estructura del clero mitraico; ya que la Iglesia Primitiva Cristiana no tenía sacerdotes, todos los creyentes eran iguales ante Dios y todos podían tomar la palabra y dirigir las asambleas en donde se recordaban las palabras de Jesús y sólo existían unos encargados de moderar y poner orden entre los asistentes. Luego se nombraron personas entre los más ancianos y respetados, para que administraran los bienes de la congregación y repartieran entre los más pobres las dádivas de los más favorecidos, pero en las primeras iglesias cristianas no existía el clero como tal.

Constantino convocó el Concilio de Nicea en el siglo IV, y lo presidió aunque no era cristiano. Los obispos o encargados de las iglesias de aquella época, se dejaron embaucar con los regalos y donaciones imperiales, así como con las promesas de nombramientos oficiales, que les equiparaban a los magistrados del imperio.

De aquél concilio presidido por un no cristiano, el emperador Constantino, nació el Cristianismo tal y como lo conocemos hoy, con Jesús convertido en Dios, segunda persona de la Santísima Trinidad y Redentor de los hombres, la estructura clerical y la mayoría de los dogmas y creencias cristianas.

A partir de ese momento, el Mitraismo fue perseguido a muerte, sus libros quemados, sus templos derribados, y en pocos años, proscrito por edicto imperial de Teodosio. No es extraño que hoy sea difícil encontrar un libro sobre esta religión que tanto ha “aportado” a nuestra cultura y nuestra forma de vivir.

No existe ningún original de los Evangelios cristianos canónicos anterior al siglo V. Todos los Evangelios fueron reescritos, interpolados, modificados y adaptados a las nuevas normas eclesiales copiadas del mitraismo. Los Evangelios originales escritos en el siglo I y II, desaparecieron tras la persecución implacable de la jerarquía imperial y eclesiástica. La figura de Jesús fue retocada para hacerla más parecida a Mitra, Dionisos, Adonis, Osiris, Krisna y otros dioses “redentores” de la Humanidad. Todos ellos murieron y resucitaron, algunos de ellos nacieron de una virgen. Adonis por ejemplo resucitaba en Primavera; Krisna estuvo muerto tres días.

En Egipto se realizaba desde tiempo inmemorial una ceremonia de iniciación, mediante la cual el neófito era atado a una cruz tumbada horizontalmente y depositado en lo más profundo del templo en donde permanecía sin luz, agua ni comida, durante tres días. Al término de su “muerte”, el neófito era sacado a la luz y proclamado nacido de nuevo.

El Cristianismo “adoptó” las fechas más importantes del mitraismo como suyas, para aprovechar la inercia y la fe de las masas que ya estaban acostumbradas a celebrarlas desde siglos. Sólo se limitaron a cambiar el nombre del dios a honrar.

Mitra, Deo Soli Invicto

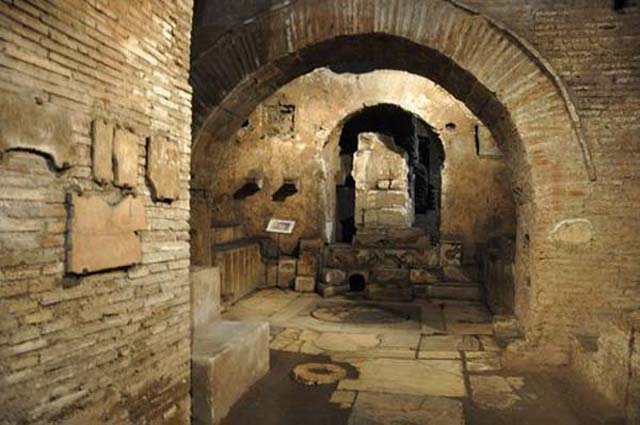

Eón mitraico, representación del tiempo cíclico infinito. Relieve de época romana.

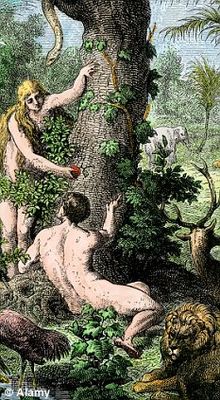

Eón mitraico, representación del tiempo cíclico infinito. Relieve de época romana."Los persas durante la ceremonia de iniciación al misterio de la bajada de las almas y de su retorno llaman caverna al lugar donde se realiza la iniciación. Según Eubolo, Zoroastro en las montañas cercanas a Persia, consagró en honor a Mitra, creador y padre de todas las cosas, un antro natural regado por manantiales y cubierto de flores y follaje. Ese antro representaba la forma del mundo creado por Mitra y las cosas que en él se encontraban, dispuestas a intervalos regulares, simbolizaban los elementos cósmicos y los climas. Después de Zoroastro se mantuvo la costumbre de realizar las ceremonias de iniciación en antros y cavernas naturales o hechos por mano del hombre. (...) No se consideraba al antro como símbolo tan sólo del mundo sensible, sino también de todas las fuerzas ocultas de la naturaleza, ya que los antros son oscuros y la esencia de dichas fuerzas es misteriosa."

Porfirio, De antro Nympharum

Ilustración idealizada del mitreo de Osterburken, Alemania, donde se representa un momento del ritual mistérico.

Ilustración idealizada del mitreo de Osterburken, Alemania, donde se representa un momento del ritual mistérico.

Dada

la gran difusión por todo el imperio romano del culto al dios de origen

iranio Mitra, sobre todo en los siglos III y IV, podemos entender que

el investigador de este periodo Ernest Renan llegara a decir: "Si el

cristianismo hubiera sido detenido por una enfermedad mortal, el mundo

hubiera sido mitraísta". Esta nueva religión mistérica fue reservada

casi exclusivamente a los soldados, impresionando a los profanos por la

disciplina, la templanza y la moral de sus miembros, virtudes propias de

la vieja tradición romana. Su difusión tuvo lugar desde Escocia a

mesopotamia y desde el Norte de África y España hasta Europa central y

los Balcanes. Se han descubierto mitreos sobre todo en las antiguas

provincias romanas de Dacia, Pannonia y Germania y se estima que en Roma

llegaron a coincidir un centenar de santuarios. En los monumentos y

obras de arte conservados sobre el mitraismo descubrimos una riquísima

iconografía, de fuerte sincretismo grecorromano con la herencia irania,

de la que esta entrada solo quiere ser una muestra. El texto que nos

servirá de guía por las imágenes seleccionadas son sobre todo los

fragmentos extraídos de la obra de Jaime Alvar Los Misterios. Religiones "orientales" en el Imperio Romano que

recomiendo para descubrir también en él los aspectos relacionados con

los sistemas rituales, sobre los que se extiende en otro capítulo.

También anotaciones de Las religiones orientales y el paganismo romano de Franz Cumont, El libro de los Símbolos de Alessandro Grossato e Historia de las creencias y de las ideas religiosas de Mircea Eliade. Las imágenes seleccionadas proceden de internet.

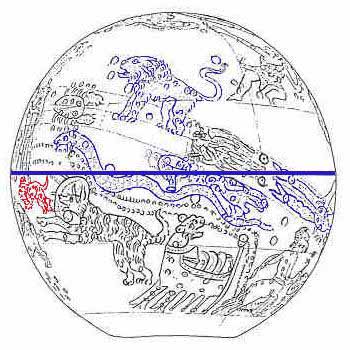

El

tema central en el mitraísmo es la escena de la tauroctonía, la muerte

de toro, en la que el joven dios, en actitud heroica clava su daga en el

cuello del animal, que ya ha doblado sus patas, mientras lo sostiene

por los orificios nasales. Así lo obliga a alzar la cabeza, pero sólo

esta, porque con la pierna izquierda doblada sobre el lomo del toro le

impide que se alce. El sacrificio del toro es un potencial de vida,

según se desprende de algunos elementos que de forma constante aparecen

en la escena. La sangre abundante que mana del cuello es lamida por un

perro, mientras se convierte en espigas de trigo (al menos en algunas

representaciones); también en espiga se ha transformado el rabo del

toro, imagen inequívoca del carácter fecundante del sacrificio. Al mismo

tiempo, un escorpión le pinza las turmas, quizá con el objeto de

apropiarse de su potencia vital, ante la presencia de un cuervo, una

serpiente -símbolo ctónico que parece actuar como anfitriona del óbito- y

un león, así como una crátera.

En esta tauroctonía se observa el rabo del toro transformado en espiga de trigo

Alrededor de esa escena, cuyo estereotipo presenta numerosas variantes excepto en la forma de representar el dios y a su víctima, hay otras muchas figuras dispuestas en arco para enmarcar el acto central: los signos zodiacales presididos por el Sol y la Luna, los planetas, los vientos, dos jóvenes portadores de antorchas llamados Cautes y Cautópates, así como otras escenas secundarias que parecen representar acontecimientos de la vida de Mitra y que constituyen motivos autónomos en algunos relieves o esculturas no vinculadas necesariamente a una representación de la tauroctonía.

Tauroctonía

del Circo Maximo, finales del siglo tercero, Roma. En la inscripción

superior se puede leer: DEI SOLI INVICTO MITHRAE TI(TUS) CL (AUDIO)

HERMES OB VOTUM DEI TYPUM D (ONUM) D (EDIT).

Tauroctonía

del Circo Maximo, finales del siglo tercero, Roma. En la inscripción

superior se puede leer: DEI SOLI INVICTO MITHRAE TI(TUS) CL (AUDIO)

HERMES OB VOTUM DEI TYPUM D (ONUM) D (EDIT).En esta versión vemos claramente también transformarse en espiga de trigo el rabo del toro. El escorpión pinza sus testículos, mientras la serpiente y el perro lamen su sangre. Sobre el gorro frigio de Mitra aparece una estrella, y otras cuatro a la derecha. Arriba a la izquierda, Helios junto a un cuervo, a la derecha la luna. Abajo a la izquierda, Mitra arrastrando al toro capturado, a su lado Cautes con la antorcha hacia arriba, en el otro extremo su gemelo Cautópates con la antorcha hacia abajo.

Cumont

fue el primero que proporcionó una narración coherente e integradora

con la documentación iconográfica, convirtiéndose en el auténtico

mitógrafo del mitraísmo, religión a la que atribuía un verdadero sistema

teológico, cuyos principios había tomado de la ciencia. En los años

setenta se discutió radicalmente la construcción de Cumont, observación

precisa para que no se tome como definitivo lo que a continuación se

relata.

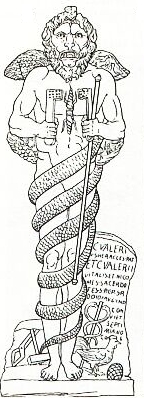

Aparentemente, del Caos original surge un dios, el Tiempo Infinito, identificado con Eón, Saeculum,

Cronos o Saturno, e incluso en ocasiones como el propio Destino. Se

representa como un joven con cabeza de león, alado y rodeado de una

serpi ente; sus atributos son el cetro y el rayo, así como la llave que lleva en cada mano (hay variantes distintas) La

imagen de la derecha es la ilustración de la estatua romana de Eón o

Aión (Mitra-Kronos) procedente del mitreo de Ostia y actualmente en los

museos vaticanos. La serpiente enrollada al cuerpo en seis roscas, y

cuya cabeza corona la escultura, simboliza el curso del sol, seis meses

en ascenso, desde el solsticio de invierno al de verano, y seis de

descenso a la inversa. Simboliza también el tiempo cíclico infinito. El

largo cetro de la mano izquierda simboliza el Axis Mundi, mientras

en la derecha sujeta "la llave del tiempo", con las marcas de los doce

meses. En el centro del pecho se encuentra el haz de rayos, a la

izquierda de sus pies, las herramientas del herrero que atribuyen el

dominio del fuego, al otro lado el caduceo el gallo y la piña. Estos dos

últimos son símbolos de fertilidad.

ente; sus atributos son el cetro y el rayo, así como la llave que lleva en cada mano (hay variantes distintas) La

imagen de la derecha es la ilustración de la estatua romana de Eón o

Aión (Mitra-Kronos) procedente del mitreo de Ostia y actualmente en los

museos vaticanos. La serpiente enrollada al cuerpo en seis roscas, y

cuya cabeza corona la escultura, simboliza el curso del sol, seis meses

en ascenso, desde el solsticio de invierno al de verano, y seis de

descenso a la inversa. Simboliza también el tiempo cíclico infinito. El

largo cetro de la mano izquierda simboliza el Axis Mundi, mientras

en la derecha sujeta "la llave del tiempo", con las marcas de los doce

meses. En el centro del pecho se encuentra el haz de rayos, a la

izquierda de sus pies, las herramientas del herrero que atribuyen el

dominio del fuego, al otro lado el caduceo el gallo y la piña. Estos dos

últimos son símbolos de fertilidad.

ente; sus atributos son el cetro y el rayo, así como la llave que lleva en cada mano (hay variantes distintas) La

imagen de la derecha es la ilustración de la estatua romana de Eón o

Aión (Mitra-Kronos) procedente del mitreo de Ostia y actualmente en los

museos vaticanos. La serpiente enrollada al cuerpo en seis roscas, y

cuya cabeza corona la escultura, simboliza el curso del sol, seis meses

en ascenso, desde el solsticio de invierno al de verano, y seis de

descenso a la inversa. Simboliza también el tiempo cíclico infinito. El

largo cetro de la mano izquierda simboliza el Axis Mundi, mientras

en la derecha sujeta "la llave del tiempo", con las marcas de los doce

meses. En el centro del pecho se encuentra el haz de rayos, a la

izquierda de sus pies, las herramientas del herrero que atribuyen el

dominio del fuego, al otro lado el caduceo el gallo y la piña. Estos dos

últimos son símbolos de fertilidad.

ente; sus atributos son el cetro y el rayo, así como la llave que lleva en cada mano (hay variantes distintas) La

imagen de la derecha es la ilustración de la estatua romana de Eón o

Aión (Mitra-Kronos) procedente del mitreo de Ostia y actualmente en los

museos vaticanos. La serpiente enrollada al cuerpo en seis roscas, y

cuya cabeza corona la escultura, simboliza el curso del sol, seis meses

en ascenso, desde el solsticio de invierno al de verano, y seis de

descenso a la inversa. Simboliza también el tiempo cíclico infinito. El

largo cetro de la mano izquierda simboliza el Axis Mundi, mientras

en la derecha sujeta "la llave del tiempo", con las marcas de los doce

meses. En el centro del pecho se encuentra el haz de rayos, a la

izquierda de sus pies, las herramientas del herrero que atribuyen el

dominio del fuego, al otro lado el caduceo el gallo y la piña. Estos dos

últimos son símbolos de fertilidad.

Este

dios primordial habría engendrado el Cielo y la Tierra, representado

por la serpiente, de los que habría nacido el Océano. Queda así

constituida una "sagrada familia" que sería la tríada suprema del

panteón mitraico. El Cielo se identifica con Zeus-Júpiter que, en un

momento determinado, recibiría de su padre Cronos-Saturno el haz de

rayos, con lo que accede el rango de dios soberano desde el que a su vez

da vida al resto de los dioses luminosos que residen en el Olimpo. A

ellos se opone un mundo tenebroso capitaneado por Ahrimán-Putón,

hermano del Cielo-Júpiter, en su condición de hijo del Tiempo Infinito.

Su cortejo de démones, representados en ocasiones como gigantes

anguípedos, intenta arrebatar a Júpiter su trono, pero es vencido y

relegado al abismo del que procedía. Estos demonios tienen acceso a la

tierra y poseen la capacidad de actuar negativamente sobre los humanos y

los impelen a obrar mal. Las

fuerzas purificadoras básicas son dos hermanos, el fuego y el agua,

representados por el león y la crátera, respectivamente. Un tercer

elemento purificador, según veremos, es la miel, asociada precisamente a

la leóntica, uno de los siete grados iniciáticos (Porfirio, La gruta de las Ninfas = De antrum Nynpharum 15).

Su importancia es tal que se consideran como auténticos elementos

divinos y, en consecuencia, poseen un destacado papel en el ritual.

También los vientos, a los que se atribuye capacidad de intervención

sobre la naturaleza, son potencias divinas. El orden cósmico estaba

representado por la constancia reierativa del Sol que recorría el Cielo

diariamente subido en su cuadriga tirado por caballos que simbolizan al

astro luminosos. Éste era objeto de veneración por los mitraístas, así

como la Luna subida en su biga que arrastran sendos toros albos. Los

planetas, partícipes asimismo de ese orden cósmico, tutelaban a los

fieles en sus diferentes grados iniciáticos.

Relieve

de Osterburken, Alemania. Arriba en las esquinas puede observarse a

"los vientos", a la izquierda el carro solar. La escena de la

tauróctonía está envuelta por diferentes escenas de la vida de Mitra y

los signos zodiacales. Abajo en el centro la crátera y al lado el león.

Se encuentra también la siguiente inscripción: D(EO) S(OLI) I(NVICTO)

M(ITHRAE) M(ER?) CATORIUS CASTRENSIS IN SUO CONS(TITUIT)

Relieve

de Osterburken, Alemania. Arriba en las esquinas puede observarse a

"los vientos", a la izquierda el carro solar. La escena de la

tauróctonía está envuelta por diferentes escenas de la vida de Mitra y

los signos zodiacales. Abajo en el centro la crátera y al lado el león.

Se encuentra también la siguiente inscripción: D(EO) S(OLI) I(NVICTO)

M(ITHRAE) M(ER?) CATORIUS CASTRENSIS IN SUO CONS(TITUIT)

.

Ahora

bien, la divinidad que en época romana se convierte en el dios central

de ese sistema de creencias es originalmente un dios indoeuropeo que

aparece en una tablilla de Bogazköy, junto a Varuna, como garante de un

tratado suscrito entre los reyes Supilulinna de Hatusa y Mitavanza de

Mitani en 1380 a.C. Mitra encarna el aspecto jurídico-sacerdotal de la

realeza; su propio nombre significa tratado. En el Rig veda indio es

junto con Varuna encargado de mantener el orden cósmico, así como de

velar por la correcta conducta religiosa y moral.

En Irán es el encargado del orden social -bajo su protectorado están los

contratos, el matrimonio, la amistad, etc.-, es juez y brazo armado de

la justicia -por actuar ante el fuego, este se convierte en su emblema-,

es el señor de los sacrificios sangrientos y de la lluvia que permite

el crecimiento de las plantas, tal como afirma el Yasht (Himno)

de Mitra, integrado en el Avesta, pero redactado verosímilmente en

época aqueménida, cuando su gran fiesta el Mitracana, se celebraba en el

equinoccio de otoño. Allí Mitra se identifica con el sol que lo ve

todo. En el dualismo zoroástrico, Mitra es luz en combate permanente con

la oscuridad y es el que hacer huir a los malos espíritus. Este dios

todopoderoso sólo ha dejado testimonio de su persistencia, tras la

desaparición del Imperio aqueménida, en algunos lugares de Anatolia,

como los reinos del Ponto y Comagene, algunos de cuyos

es el encargado del orden social -bajo su protectorado están los

contratos, el matrimonio, la amistad, etc.-, es juez y brazo armado de

la justicia -por actuar ante el fuego, este se convierte en su emblema-,

es el señor de los sacrificios sangrientos y de la lluvia que permite

el crecimiento de las plantas, tal como afirma el Yasht (Himno)

de Mitra, integrado en el Avesta, pero redactado verosímilmente en

época aqueménida, cuando su gran fiesta el Mitracana, se celebraba en el

equinoccio de otoño. Allí Mitra se identifica con el sol que lo ve

todo. En el dualismo zoroástrico, Mitra es luz en combate permanente con

la oscuridad y es el que hacer huir a los malos espíritus. Este dios

todopoderoso sólo ha dejado testimonio de su persistencia, tras la

desaparición del Imperio aqueménida, en algunos lugares de Anatolia,

como los reinos del Ponto y Comagene, algunos de cuyos  monarcas

llevaron el nombre teóforo de Mitrídates. A pesar de ello, la

continuidad del culto iranio en el romano es muy dificil de establecer.Tanto

por las representaciones como por la información literaria, sabemos que

Mitra había nacido milagrosamente de una roca. Con frecuencia, esta

adquiere forma de huevo, lo que hace disminuir las dudas sobre la

influencia del orfismo en el Mitra romano, ratificada por el sincretismo

de Mitra con Fanetón (Fanes), la deidad órfica de la luminosidad

ilimitada que surge del huevo cósmico (ver imagen de cabecera de esta

entrada). Se trata de la piedra primigenia, el mundo embrionario

sometido al influjo de las constelaciones. Es, pues, el primer paso del mito en el necesario ordenamiento astral del cual Mitra es creador y Kosmocrator, como

afirma una inscripción de Roma. Es más, un relieve de Tréveris

representa el nacimiento, pero Mitra con su mano derecha hace girar

medio disco zodiacal, mientras q

monarcas

llevaron el nombre teóforo de Mitrídates. A pesar de ello, la

continuidad del culto iranio en el romano es muy dificil de establecer.Tanto

por las representaciones como por la información literaria, sabemos que

Mitra había nacido milagrosamente de una roca. Con frecuencia, esta

adquiere forma de huevo, lo que hace disminuir las dudas sobre la

influencia del orfismo en el Mitra romano, ratificada por el sincretismo

de Mitra con Fanetón (Fanes), la deidad órfica de la luminosidad

ilimitada que surge del huevo cósmico (ver imagen de cabecera de esta

entrada). Se trata de la piedra primigenia, el mundo embrionario

sometido al influjo de las constelaciones. Es, pues, el primer paso del mito en el necesario ordenamiento astral del cual Mitra es creador y Kosmocrator, como

afirma una inscripción de Roma. Es más, un relieve de Tréveris

representa el nacimiento, pero Mitra con su mano derecha hace girar

medio disco zodiacal, mientras q ue

con la izquierda sostiene el globo terráqueo. Por otra parte, un

relieve del mitreo de Poetovio (imagen izquierda) de mediados del siglo

III complica aun más la escena, pues Mitra es ayudado a salir de la roca

por dos personajes, presumiblemente Cautes y Cautópes. Sobre ellos, en

un registro superior, duerme un anciano, seguramente Saturno, al que

corona una victoria. Puede tratarse de la representación del sueño

premonitorio en el que se anuncia el nacimiento del invicto Mitra; pero

podría tratarse de un testimonio de la secuencia del tiempo y de la

sucesión de las eras en una hipotética cronografía mítica mitraíca, ya

que la era del Tiempo Infinito es sucedida por la hegemonía de Mitra,

reconocido como Saecularis que proporciona la victoria sobre el

mal y el descanso cósmico. Como parte de esa cronografía habría que

entender la presencia del Sol y la Luna, como axpresión de la secuencia

del día y la noche, de los planetas, que simbolizan los días y, por lo

tanto, la seuencia semanal, del zodíaco como secuencia del año, y así

sucesivamente. La

relevancia del acontecimiento puede constatarse en el hecho de que Mitra

saxígeno es la representación más frecuente en el mitraísmo tras la

tauroctonía. En el nacimiento de Mitra está el origen de todas las

cosas; pero en primer lugar está el origen de la luz, como se desprende

de la asociación, mediante llamas o antorchas, del fuego con el saxígeno

y su identificación con el dios de la luz Fanetón. Unos pastores habían presenciado el acontecimiento por el que el niño desnudo

ue

con la izquierda sostiene el globo terráqueo. Por otra parte, un

relieve del mitreo de Poetovio (imagen izquierda) de mediados del siglo

III complica aun más la escena, pues Mitra es ayudado a salir de la roca

por dos personajes, presumiblemente Cautes y Cautópes. Sobre ellos, en

un registro superior, duerme un anciano, seguramente Saturno, al que

corona una victoria. Puede tratarse de la representación del sueño

premonitorio en el que se anuncia el nacimiento del invicto Mitra; pero

podría tratarse de un testimonio de la secuencia del tiempo y de la

sucesión de las eras en una hipotética cronografía mítica mitraíca, ya

que la era del Tiempo Infinito es sucedida por la hegemonía de Mitra,

reconocido como Saecularis que proporciona la victoria sobre el

mal y el descanso cósmico. Como parte de esa cronografía habría que

entender la presencia del Sol y la Luna, como axpresión de la secuencia

del día y la noche, de los planetas, que simbolizan los días y, por lo

tanto, la seuencia semanal, del zodíaco como secuencia del año, y así

sucesivamente. La

relevancia del acontecimiento puede constatarse en el hecho de que Mitra

saxígeno es la representación más frecuente en el mitraísmo tras la

tauroctonía. En el nacimiento de Mitra está el origen de todas las

cosas; pero en primer lugar está el origen de la luz, como se desprende

de la asociación, mediante llamas o antorchas, del fuego con el saxígeno

y su identificación con el dios de la luz Fanetón. Unos pastores habían presenciado el acontecimiento por el que el niño desnudo  surge

tocado con el característico gorro frigio y con una antorcha en una

mano y el cuchillo sacrificial en la otra. El fuego lo caracteriza como

deidad solar, pero también como dador de luz a sus protegidos; el

cuchillo es el instrumento por el que da vida mediante la muerte de

toro, por ello en alguna ocasión el cuchillo es sustituido abiertamente

por una espiga de trigo. Incluso en una ocasión la escena del nacimiento

se encuentra enmarcada exactamente como si de la tauroctonía se

tratara, lo que permite entender la leyenda de Mitra como una estructura

cerrada, no lineal, por cuanto lo más importante son los efectos que

sus vicisitudes procuran al género humano. En este sentido, la roca no

es sólo el mundo, sino el universo, contiene un significado análogo al

de la caverna en la que tiene lugar el sacrificio del toro, simbolismo

que a su vez se reproduce en el mitreo. En cualquier caso, los pastores

acuden a ofrecerle sus primicias y a rendirle adoración, lo que incide

en la función de Mitra como protector de la humanidad. En algu

surge

tocado con el característico gorro frigio y con una antorcha en una

mano y el cuchillo sacrificial en la otra. El fuego lo caracteriza como

deidad solar, pero también como dador de luz a sus protegidos; el

cuchillo es el instrumento por el que da vida mediante la muerte de

toro, por ello en alguna ocasión el cuchillo es sustituido abiertamente

por una espiga de trigo. Incluso en una ocasión la escena del nacimiento

se encuentra enmarcada exactamente como si de la tauroctonía se

tratara, lo que permite entender la leyenda de Mitra como una estructura

cerrada, no lineal, por cuanto lo más importante son los efectos que

sus vicisitudes procuran al género humano. En este sentido, la roca no

es sólo el mundo, sino el universo, contiene un significado análogo al

de la caverna en la que tiene lugar el sacrificio del toro, simbolismo

que a su vez se reproduce en el mitreo. En cualquier caso, los pastores

acuden a ofrecerle sus primicias y a rendirle adoración, lo que incide

en la función de Mitra como protector de la humanidad. En algu nas

ocasiones la escena del nacimiento se representa con variantes. Un

ejemplo llamativo es el que proporciona un relieve del mitreo I de

Heddernheim, en el que la roca ha sido sustituida directamente por un

árbol, tal vez como consecuencia de la previa identificaación de la roca

con una piña; aunque en los frescos de Hawarte aparece tanto la escena

saxígena como Mitra sobre el ciprés. Al parecer, el énfasis se ha

desplazado desde el simbolismo cósmico a la vegetación, para incidir aún

más intensamente en el carácter de dios protector de la naturaleza que

en algunas regiones se otorga a Mitra y en especial de la producción

agrícola, como se desprende de otras representaciones iconográficas y de

la mención que de él hace Porfirio (de antro) como "guardián de los frutos". Pero, al mismo tiempo, el testimonio de Heidernheim puede contribuir al

nas

ocasiones la escena del nacimiento se representa con variantes. Un

ejemplo llamativo es el que proporciona un relieve del mitreo I de

Heddernheim, en el que la roca ha sido sustituida directamente por un

árbol, tal vez como consecuencia de la previa identificaación de la roca

con una piña; aunque en los frescos de Hawarte aparece tanto la escena

saxígena como Mitra sobre el ciprés. Al parecer, el énfasis se ha

desplazado desde el simbolismo cósmico a la vegetación, para incidir aún

más intensamente en el carácter de dios protector de la naturaleza que

en algunas regiones se otorga a Mitra y en especial de la producción

agrícola, como se desprende de otras representaciones iconográficas y de

la mención que de él hace Porfirio (de antro) como "guardián de los frutos". Pero, al mismo tiempo, el testimonio de Heidernheim puede contribuir al  desciframiento

del relieve de Dieburg en el que aparecen tres cabezas tocadas con

gorro frigio colgadas de un árbol; puesto que en otras ocasiones Cautes y

Cautópates aparecen relacionados con el nacimiento de Mitra, tal vez en

Dieburg tenemos una versión local del nacimiento de Mitra acompañado

por los portadores de antorchas. No es fácil determinar quíenes son en

realidad Cautes y Cautópates; su parecido iconográfico a Mitra es

extraordinario. Pero es probable que hubieran llegado a representar

alegorías diferentes. Por un lado, como habitualmente aparecen

flanqueando a Mitra y uno, Cautes, lleva la antorcha hacia arriba

mientras el otro la tiene hacia abajo, se supone que representan al sol

matutino y vespertino, respectivamente, siendo Mitra el sol cenital.

Pero también Cautes parece asociado al cielo y Cautópates al Océano, por

donde se produce el ocaso del sol. De ahí que se interpreten como

Oriente y Occidente e incluso que se asocien, respectivamente, al Sol y

Luna y, como consecuencia, representen la oposición vida/muerte. Es

precisamente esta última dirección en la que se han realizado las

aportaciones más interesantes en los últimos años gracias a la

perspicacia anlítica de Beck y Gordon. La lectura crítica de Porfirio

sugerida por Beck en combinación con el significado conceptual de la

fisionomía de los mitreos formulados por Gordon, permite asumir que los

gemelos son los agentes de Mitra que controlan las puertas por las que

se produce el descenso de las almas desde las estrellas hasta el mundo

de los mortales y su ascenso a la inmortalidad a través del itinerario

estelar. (Los portadores de antorchas señalarían los solsticios de

verano, Cautopátes, y de invierno, Cautes.

desciframiento

del relieve de Dieburg en el que aparecen tres cabezas tocadas con

gorro frigio colgadas de un árbol; puesto que en otras ocasiones Cautes y

Cautópates aparecen relacionados con el nacimiento de Mitra, tal vez en

Dieburg tenemos una versión local del nacimiento de Mitra acompañado

por los portadores de antorchas. No es fácil determinar quíenes son en

realidad Cautes y Cautópates; su parecido iconográfico a Mitra es

extraordinario. Pero es probable que hubieran llegado a representar

alegorías diferentes. Por un lado, como habitualmente aparecen

flanqueando a Mitra y uno, Cautes, lleva la antorcha hacia arriba

mientras el otro la tiene hacia abajo, se supone que representan al sol

matutino y vespertino, respectivamente, siendo Mitra el sol cenital.

Pero también Cautes parece asociado al cielo y Cautópates al Océano, por

donde se produce el ocaso del sol. De ahí que se interpreten como

Oriente y Occidente e incluso que se asocien, respectivamente, al Sol y

Luna y, como consecuencia, representen la oposición vida/muerte. Es

precisamente esta última dirección en la que se han realizado las

aportaciones más interesantes en los últimos años gracias a la

perspicacia anlítica de Beck y Gordon. La lectura crítica de Porfirio

sugerida por Beck en combinación con el significado conceptual de la

fisionomía de los mitreos formulados por Gordon, permite asumir que los

gemelos son los agentes de Mitra que controlan las puertas por las que

se produce el descenso de las almas desde las estrellas hasta el mundo

de los mortales y su ascenso a la inmortalidad a través del itinerario

estelar. (Los portadores de antorchas señalarían los solsticios de

verano, Cautopátes, y de invierno, Cautes.

En Irán

es el encargado del orden social -bajo su protectorado están los

contratos, el matrimonio, la amistad, etc.-, es juez y brazo armado de

la justicia -por actuar ante el fuego, este se convierte en su emblema-,

es el señor de los sacrificios sangrientos y de la lluvia que permite

el crecimiento de las plantas, tal como afirma el Yasht (Himno)

de Mitra, integrado en el Avesta, pero redactado verosímilmente en

época aqueménida, cuando su gran fiesta el Mitracana, se celebraba en el

equinoccio de otoño. Allí Mitra se identifica con el sol que lo ve

todo. En el dualismo zoroástrico, Mitra es luz en combate permanente con

la oscuridad y es el que hacer huir a los malos espíritus. Este dios

todopoderoso sólo ha dejado testimonio de su persistencia, tras la

desaparición del Imperio aqueménida, en algunos lugares de Anatolia,

como los reinos del Ponto y Comagene, algunos de cuyos

es el encargado del orden social -bajo su protectorado están los

contratos, el matrimonio, la amistad, etc.-, es juez y brazo armado de

la justicia -por actuar ante el fuego, este se convierte en su emblema-,

es el señor de los sacrificios sangrientos y de la lluvia que permite

el crecimiento de las plantas, tal como afirma el Yasht (Himno)

de Mitra, integrado en el Avesta, pero redactado verosímilmente en

época aqueménida, cuando su gran fiesta el Mitracana, se celebraba en el

equinoccio de otoño. Allí Mitra se identifica con el sol que lo ve

todo. En el dualismo zoroástrico, Mitra es luz en combate permanente con

la oscuridad y es el que hacer huir a los malos espíritus. Este dios

todopoderoso sólo ha dejado testimonio de su persistencia, tras la

desaparición del Imperio aqueménida, en algunos lugares de Anatolia,

como los reinos del Ponto y Comagene, algunos de cuyos  monarcas

llevaron el nombre teóforo de Mitrídates. A pesar de ello, la

continuidad del culto iranio en el romano es muy dificil de establecer.Tanto

por las representaciones como por la información literaria, sabemos que

Mitra había nacido milagrosamente de una roca. Con frecuencia, esta

adquiere forma de huevo, lo que hace disminuir las dudas sobre la

influencia del orfismo en el Mitra romano, ratificada por el sincretismo

de Mitra con Fanetón (Fanes), la deidad órfica de la luminosidad

ilimitada que surge del huevo cósmico (ver imagen de cabecera de esta

entrada). Se trata de la piedra primigenia, el mundo embrionario

sometido al influjo de las constelaciones. Es, pues, el primer paso del mito en el necesario ordenamiento astral del cual Mitra es creador y Kosmocrator, como

afirma una inscripción de Roma. Es más, un relieve de Tréveris

representa el nacimiento, pero Mitra con su mano derecha hace girar

medio disco zodiacal, mientras q

monarcas

llevaron el nombre teóforo de Mitrídates. A pesar de ello, la

continuidad del culto iranio en el romano es muy dificil de establecer.Tanto

por las representaciones como por la información literaria, sabemos que

Mitra había nacido milagrosamente de una roca. Con frecuencia, esta

adquiere forma de huevo, lo que hace disminuir las dudas sobre la

influencia del orfismo en el Mitra romano, ratificada por el sincretismo

de Mitra con Fanetón (Fanes), la deidad órfica de la luminosidad

ilimitada que surge del huevo cósmico (ver imagen de cabecera de esta

entrada). Se trata de la piedra primigenia, el mundo embrionario

sometido al influjo de las constelaciones. Es, pues, el primer paso del mito en el necesario ordenamiento astral del cual Mitra es creador y Kosmocrator, como

afirma una inscripción de Roma. Es más, un relieve de Tréveris

representa el nacimiento, pero Mitra con su mano derecha hace girar

medio disco zodiacal, mientras q ue

con la izquierda sostiene el globo terráqueo. Por otra parte, un

relieve del mitreo de Poetovio (imagen izquierda) de mediados del siglo

III complica aun más la escena, pues Mitra es ayudado a salir de la roca

por dos personajes, presumiblemente Cautes y Cautópes. Sobre ellos, en

un registro superior, duerme un anciano, seguramente Saturno, al que

corona una victoria. Puede tratarse de la representación del sueño

premonitorio en el que se anuncia el nacimiento del invicto Mitra; pero

podría tratarse de un testimonio de la secuencia del tiempo y de la

sucesión de las eras en una hipotética cronografía mítica mitraíca, ya

que la era del Tiempo Infinito es sucedida por la hegemonía de Mitra,

reconocido como Saecularis que proporciona la victoria sobre el

mal y el descanso cósmico. Como parte de esa cronografía habría que

entender la presencia del Sol y la Luna, como axpresión de la secuencia

del día y la noche, de los planetas, que simbolizan los días y, por lo

tanto, la seuencia semanal, del zodíaco como secuencia del año, y así

sucesivamente. La

relevancia del acontecimiento puede constatarse en el hecho de que Mitra

saxígeno es la representación más frecuente en el mitraísmo tras la

tauroctonía. En el nacimiento de Mitra está el origen de todas las

cosas; pero en primer lugar está el origen de la luz, como se desprende

de la asociación, mediante llamas o antorchas, del fuego con el saxígeno

y su identificación con el dios de la luz Fanetón. Unos pastores habían presenciado el acontecimiento por el que el niño desnudo

ue

con la izquierda sostiene el globo terráqueo. Por otra parte, un

relieve del mitreo de Poetovio (imagen izquierda) de mediados del siglo

III complica aun más la escena, pues Mitra es ayudado a salir de la roca

por dos personajes, presumiblemente Cautes y Cautópes. Sobre ellos, en

un registro superior, duerme un anciano, seguramente Saturno, al que

corona una victoria. Puede tratarse de la representación del sueño

premonitorio en el que se anuncia el nacimiento del invicto Mitra; pero

podría tratarse de un testimonio de la secuencia del tiempo y de la

sucesión de las eras en una hipotética cronografía mítica mitraíca, ya

que la era del Tiempo Infinito es sucedida por la hegemonía de Mitra,

reconocido como Saecularis que proporciona la victoria sobre el

mal y el descanso cósmico. Como parte de esa cronografía habría que

entender la presencia del Sol y la Luna, como axpresión de la secuencia

del día y la noche, de los planetas, que simbolizan los días y, por lo

tanto, la seuencia semanal, del zodíaco como secuencia del año, y así

sucesivamente. La

relevancia del acontecimiento puede constatarse en el hecho de que Mitra

saxígeno es la representación más frecuente en el mitraísmo tras la

tauroctonía. En el nacimiento de Mitra está el origen de todas las

cosas; pero en primer lugar está el origen de la luz, como se desprende

de la asociación, mediante llamas o antorchas, del fuego con el saxígeno

y su identificación con el dios de la luz Fanetón. Unos pastores habían presenciado el acontecimiento por el que el niño desnudo  surge

tocado con el característico gorro frigio y con una antorcha en una

mano y el cuchillo sacrificial en la otra. El fuego lo caracteriza como

deidad solar, pero también como dador de luz a sus protegidos; el

cuchillo es el instrumento por el que da vida mediante la muerte de

toro, por ello en alguna ocasión el cuchillo es sustituido abiertamente

por una espiga de trigo. Incluso en una ocasión la escena del nacimiento

se encuentra enmarcada exactamente como si de la tauroctonía se

tratara, lo que permite entender la leyenda de Mitra como una estructura

cerrada, no lineal, por cuanto lo más importante son los efectos que

sus vicisitudes procuran al género humano. En este sentido, la roca no

es sólo el mundo, sino el universo, contiene un significado análogo al

de la caverna en la que tiene lugar el sacrificio del toro, simbolismo

que a su vez se reproduce en el mitreo. En cualquier caso, los pastores

acuden a ofrecerle sus primicias y a rendirle adoración, lo que incide

en la función de Mitra como protector de la humanidad. En algu

surge

tocado con el característico gorro frigio y con una antorcha en una

mano y el cuchillo sacrificial en la otra. El fuego lo caracteriza como

deidad solar, pero también como dador de luz a sus protegidos; el

cuchillo es el instrumento por el que da vida mediante la muerte de

toro, por ello en alguna ocasión el cuchillo es sustituido abiertamente

por una espiga de trigo. Incluso en una ocasión la escena del nacimiento

se encuentra enmarcada exactamente como si de la tauroctonía se

tratara, lo que permite entender la leyenda de Mitra como una estructura

cerrada, no lineal, por cuanto lo más importante son los efectos que

sus vicisitudes procuran al género humano. En este sentido, la roca no

es sólo el mundo, sino el universo, contiene un significado análogo al

de la caverna en la que tiene lugar el sacrificio del toro, simbolismo

que a su vez se reproduce en el mitreo. En cualquier caso, los pastores

acuden a ofrecerle sus primicias y a rendirle adoración, lo que incide

en la función de Mitra como protector de la humanidad. En algu nas

ocasiones la escena del nacimiento se representa con variantes. Un

ejemplo llamativo es el que proporciona un relieve del mitreo I de

Heddernheim, en el que la roca ha sido sustituida directamente por un

árbol, tal vez como consecuencia de la previa identificaación de la roca

con una piña; aunque en los frescos de Hawarte aparece tanto la escena

saxígena como Mitra sobre el ciprés. Al parecer, el énfasis se ha

desplazado desde el simbolismo cósmico a la vegetación, para incidir aún

más intensamente en el carácter de dios protector de la naturaleza que

en algunas regiones se otorga a Mitra y en especial de la producción

agrícola, como se desprende de otras representaciones iconográficas y de

la mención que de él hace Porfirio (de antro) como "guardián de los frutos". Pero, al mismo tiempo, el testimonio de Heidernheim puede contribuir al

nas

ocasiones la escena del nacimiento se representa con variantes. Un

ejemplo llamativo es el que proporciona un relieve del mitreo I de

Heddernheim, en el que la roca ha sido sustituida directamente por un

árbol, tal vez como consecuencia de la previa identificaación de la roca

con una piña; aunque en los frescos de Hawarte aparece tanto la escena

saxígena como Mitra sobre el ciprés. Al parecer, el énfasis se ha

desplazado desde el simbolismo cósmico a la vegetación, para incidir aún

más intensamente en el carácter de dios protector de la naturaleza que

en algunas regiones se otorga a Mitra y en especial de la producción

agrícola, como se desprende de otras representaciones iconográficas y de

la mención que de él hace Porfirio (de antro) como "guardián de los frutos". Pero, al mismo tiempo, el testimonio de Heidernheim puede contribuir al  desciframiento

del relieve de Dieburg en el que aparecen tres cabezas tocadas con

gorro frigio colgadas de un árbol; puesto que en otras ocasiones Cautes y

Cautópates aparecen relacionados con el nacimiento de Mitra, tal vez en

Dieburg tenemos una versión local del nacimiento de Mitra acompañado

por los portadores de antorchas. No es fácil determinar quíenes son en

realidad Cautes y Cautópates; su parecido iconográfico a Mitra es

extraordinario. Pero es probable que hubieran llegado a representar

alegorías diferentes. Por un lado, como habitualmente aparecen

flanqueando a Mitra y uno, Cautes, lleva la antorcha hacia arriba

mientras el otro la tiene hacia abajo, se supone que representan al sol

matutino y vespertino, respectivamente, siendo Mitra el sol cenital.

Pero también Cautes parece asociado al cielo y Cautópates al Océano, por

donde se produce el ocaso del sol. De ahí que se interpreten como

Oriente y Occidente e incluso que se asocien, respectivamente, al Sol y

Luna y, como consecuencia, representen la oposición vida/muerte. Es

precisamente esta última dirección en la que se han realizado las

aportaciones más interesantes en los últimos años gracias a la

perspicacia anlítica de Beck y Gordon. La lectura crítica de Porfirio

sugerida por Beck en combinación con el significado conceptual de la

fisionomía de los mitreos formulados por Gordon, permite asumir que los

gemelos son los agentes de Mitra que controlan las puertas por las que

se produce el descenso de las almas desde las estrellas hasta el mundo

de los mortales y su ascenso a la inmortalidad a través del itinerario

estelar. (Los portadores de antorchas señalarían los solsticios de

verano, Cautopátes, y de invierno, Cautes.

desciframiento

del relieve de Dieburg en el que aparecen tres cabezas tocadas con

gorro frigio colgadas de un árbol; puesto que en otras ocasiones Cautes y

Cautópates aparecen relacionados con el nacimiento de Mitra, tal vez en

Dieburg tenemos una versión local del nacimiento de Mitra acompañado

por los portadores de antorchas. No es fácil determinar quíenes son en

realidad Cautes y Cautópates; su parecido iconográfico a Mitra es

extraordinario. Pero es probable que hubieran llegado a representar

alegorías diferentes. Por un lado, como habitualmente aparecen

flanqueando a Mitra y uno, Cautes, lleva la antorcha hacia arriba

mientras el otro la tiene hacia abajo, se supone que representan al sol

matutino y vespertino, respectivamente, siendo Mitra el sol cenital.

Pero también Cautes parece asociado al cielo y Cautópates al Océano, por

donde se produce el ocaso del sol. De ahí que se interpreten como

Oriente y Occidente e incluso que se asocien, respectivamente, al Sol y

Luna y, como consecuencia, representen la oposición vida/muerte. Es

precisamente esta última dirección en la que se han realizado las

aportaciones más interesantes en los últimos años gracias a la

perspicacia anlítica de Beck y Gordon. La lectura crítica de Porfirio

sugerida por Beck en combinación con el significado conceptual de la

fisionomía de los mitreos formulados por Gordon, permite asumir que los

gemelos son los agentes de Mitra que controlan las puertas por las que

se produce el descenso de las almas desde las estrellas hasta el mundo

de los mortales y su ascenso a la inmortalidad a través del itinerario

estelar. (Los portadores de antorchas señalarían los solsticios de

verano, Cautopátes, y de invierno, Cautes. En el primero se produciría el descenso del alma a la tierra (génesis) y en el segundo el ascenso (apogénesis); por su parte, Mitra se situaría de forma equidistante en los equinoccios). En realidad, estos hermanos gemelos, que están ya presentes en el nacimiento de Mitra y, por lo tanto, en los orígenes de la creación, podrían ser representaciones del mismo dios, lo que permite comprender el término triplasios ("triple") que en el siglo VI aplica a Mitra Dionisio Areopagita (Epist. 7,2) y que ilustra el árbol con las cabezas de Dieburg, con lo que concluimos esta disgresión que nos sitúa ante la posibilidad de una realidad tricorporea para este dios, una inesperada trinida, cuya relevancia en el universo de las creencias mitraicas está ensombrecida por el silencio. Otro de los avatares de Mitra es su victoria sobre el toro, al que somete tras galopar sobre su grupa y después de haberlo asido por los cuernos hasta doblegarlo.

En

algunas escenas se representa a Mitra arrastrando al toro por sus

cuartos traseros para conducirlo hasta la cueva que le servía de

guarida. En el camino encuentra numerosos obstáculos, como si de un rito

de tránsito se tratara, alegoría de las pruebas que han de superar los

humanos. Un cuervo transmite a Mitra un mensaje del Sol por el que le

insta a matar al toro. El encargo es fielmente acometido, tal como se

reproduce en la escena de la tauroctonía. Ésta se ha interpretado como

la creación de todos los seres benéficos, lo que convierte a mitra en un

verdadero dios creador. Pero antes del acto sublime del sacrificio del

toro, Mitra habría logrado algunos triunfos frente a Ahrimán, que

pretendía aniquilar a los humanos, según la versión de Cumont. En cierta

ocasión provoca tal sequía que obliga a la intervención de su rival.

Mitra dispara una flecha contra una roca de la que mana agua cristalina,

con la que salva a sus protegidos y se convierte en una divinidad

protectora del agua.

En

algunas escenas se representa a Mitra arrastrando al toro por sus

cuartos traseros para conducirlo hasta la cueva que le servía de

guarida. En el camino encuentra numerosos obstáculos, como si de un rito

de tránsito se tratara, alegoría de las pruebas que han de superar los

humanos. Un cuervo transmite a Mitra un mensaje del Sol por el que le

insta a matar al toro. El encargo es fielmente acometido, tal como se

reproduce en la escena de la tauroctonía. Ésta se ha interpretado como

la creación de todos los seres benéficos, lo que convierte a mitra en un

verdadero dios creador. Pero antes del acto sublime del sacrificio del

toro, Mitra habría logrado algunos triunfos frente a Ahrimán, que

pretendía aniquilar a los humanos, según la versión de Cumont. En cierta

ocasión provoca tal sequía que obliga a la intervención de su rival.

Mitra dispara una flecha contra una roca de la que mana agua cristalina,

con la que salva a sus protegidos y se convierte en una divinidad

protectora del agua.En un ara de Poetovio Cautes y Cautópes aparecen acompañando a Mitra en este episodio que se ha relacionado con una de las frases escritas en las paredes del mitreo de Santa Prisca en Roma, según la cual los hermanos gemelos habrían sido alimentados con el nectar de la fuente surgida de la roca.(...) El nectar con el que se alimentan los gemelos podría ser coincidente con la sangre eterna que salva, como reza la oración de Santa Prisca tantas veces mendionada: "Y nos salvaste con el derramamiento de la sangre (eterna)". Liquido manado de la "fons perennis" que es elpropio Mitra (así lo denomina una inscripción de Petovio. Pero eso no es todo. Porfirio asevera que la crátera es el símbolo de la fuente y que por ello en Mitra la crátera sustituye a la fuente (De antro); así pues, podemos asumir que la representación de la crátera en la tauroctonía es un símbolo del llamado "milagro del agua", que adquiere así su verdadera posición cosmogónica, no como un episodio en la vida de Mitra, sino como auténtica rememoración de la creación del agua, simbolismo de los fluidos dadores de vida.(...) Garantizada la seguridad de los mortales, Mitra da por concluida su misión en la tierra. Para celebrarlo se realiza un ágape supremo en el que los comensales de honor son Helios y Mitra, pero en el que, además, participan los principales compañeros de aventuras. Una vez saciados, los dos amigos suben a la cuadriga que ha de conducirlos, en una verdadera apoteosis, junto a los restantes dioses, donde Mitra se instala como protector de sus fieles servidores.

Relieve

en marmol con escena del ágape supremo. En él reconocemos la piel del

toro sacrificado en el que se reclinan Helios y Mitra. A la izquierda

aparece la Luna y abajo Cautes ofrece un ritón a Helios, mientras

Cautóptes, a la derecha dirige el caduceo al nectar de la fuente que

brota de la roca.

Relieve

en marmol con escena del ágape supremo. En él reconocemos la piel del

toro sacrificado en el que se reclinan Helios y Mitra. A la izquierda

aparece la Luna y abajo Cautes ofrece un ritón a Helios, mientras

Cautóptes, a la derecha dirige el caduceo al nectar de la fuente que

brota de la roca.(The following article is adapted from a chapter in Suns of God: Krishna, Buddha and Christ Unveiled, as well as excerpts from othre articles, such as "The Origins of Christianity" and "The ZEITGEIST Sourcebook.")

"Both Mithras and Christ were described variously as 'the Way,' 'the Truth,' 'the Light,' 'the Life,' 'the Word,' 'the Son of God,' 'the Good Shepherd.' The Christian litany to Jesus could easily be an allegorical litany to the sun-god. Mithras is often represented as carrying a lamb on his shoulders, just as Jesus is. Midnight services were found in both religions. The virgin mother...was easily merged with the virgin mother Mary. Petra, the sacred rock of Mithraism, became Peter, the foundation of the Christian Church."

Gerald Berry, Religions of the World

"Mithra or Mitra is...worshipped as Itu (Mitra-Mitu-Itu) in every house of the Hindus in India. Itu (derivative of Mitu or Mitra) is considered as the Vegetation-deity. This Mithra or Mitra (Sun-God) is believed to be a Mediator between God and man, between the Sky and the Earth. It is said that Mithra or [the] Sun took birth in the Cave on December 25th. It is also the belief of the Christian world that Mithra or the Sun-God was born of [a] Virgin. He travelled far and wide. He has twelve satellites, which are taken as the Sun's disciples.... [The Sun's] great festivals are observed in the Winter Solstice and the Vernal Equinox—Christmas and Easter. His symbol is the Lamb...."

Swami Prajnanananda, Christ the Saviour and Christ Myth

Because of its evident relationship to Christianity, special attention needs to be paid to the Persian/Roman religion of Mithraism. The worship of the Indo-Persian god Mithra dates back centuries to millennia preceding the common era. The god is found as "Mitra" in the Indian Vedic religion, which is over 3,500 years old, by conservative estimates. When the Iranians separated from their Indian brethren, Mitra became known as "Mithra" or "Mihr," as he is also called in Persian.

By around 1500 BCE, Mithra worship had made it to the Near East, in the Indian kingdom of the Mitanni, who at that time occupied Assyria. Mithra worship, however, was known also by that time as far west as the Hittite kingdom, only a few hundred miles east of the Mediterranean, as is evidenced by the Hittite-Mitanni tablets found at Bogaz-Köy in what is now Turkey. The gods of the Mitanni included Mitra, Varuna and Indra, all found in the Vedic texts.

By around 1500 BCE, Mithra worship had made it to the Near East, in the Indian kingdom of the Mitanni, who at that time occupied Assyria. Mithra worship, however, was known also by that time as far west as the Hittite kingdom, only a few hundred miles east of the Mediterranean, as is evidenced by the Hittite-Mitanni tablets found at Bogaz-Köy in what is now Turkey. The gods of the Mitanni included Mitra, Varuna and Indra, all found in the Vedic texts.Mithra as Sun God

The Indian Mitra was essentially a solar deity, representing the "friendly" aspect of the sun. So too was the Persian derivative Mithra, who was a "benevolent god" and the bestower of health, wealth and food. Mithra also seems to have been looked upon as a sort of Prometheus, for the gift of fire. (Schironi, 104) His worship purified and freed the devotee from sin and disease. Eventually, Mithra became more militant, and he is best known as a warrior.

Like so many gods, Mithra was the light and power behind the sun. In Babylon, Mithra was identified with Shamash, the sun god, and he is also Bel, the Mesopotamian and Canaanite/ Phoenician solar deity, who is likewise Marduk, the Babylonian god who represented both the planet Jupiter and the sun. According to Pseudo-Clement of Rome's debate with Appion (Homily VI, ch. X), Mithra is also Apollo.

Like so many gods, Mithra was the light and power behind the sun. In Babylon, Mithra was identified with Shamash, the sun god, and he is also Bel, the Mesopotamian and Canaanite/ Phoenician solar deity, who is likewise Marduk, the Babylonian god who represented both the planet Jupiter and the sun. According to Pseudo-Clement of Rome's debate with Appion (Homily VI, ch. X), Mithra is also Apollo.

In time, the Persian Mithraism became infused with the more detailed astrotheology of the Babylonians and Chaldeans, and was notable for its astrology and magic; indeed, its priests or magi lent their very name to the word "magic." Included in this astrotheological development was the re-emphasis on Mithra's early Indian role as a sun god. As Francis Legge says in Forerunners and Rivals in Christianity:

The Vedic Mitra was originally the material sun itself, and the many hundreds of votive inscriptions left by the worshippers of Mithras to "the unconquered Sun Mithras," to the unconquered solar divinity (numen) Mithras, to the unconquered Sun-God (deus) Mithra, and allusions in them to priests (sacerdotes), worshippers (cultores), and temples (templum) of the same deity leave no doubt open that he was in Roman times a sun-god. (Legge, II, 240)

By the Roman legionnaires, Mithra—or Mithras, as he began to be known in the Greco-Roman world—was called "the divine Sun, the Unconquered Sun." He was said to be "Mighty in strength, mighty ruler, greatest king of gods! O Sun, lord of heaven and earth, God of Gods!" Mithra was also deemed "the mediator" between heaven and earth, a role often ascribed to the god of the sun.

An inscription by a "T. Flavius Hyginus" dating to around 80 to 100 AD/CE in Rome dedicates an altar to "Sol Invictus Mithras"—"The Unconquered Sun Mithra"—revealing the hybridization reflected in other artifacts and myths. Regarding this title, Dr. Richard L. Gordon, honorary professor of Religionsgeschichte der Antike at the University of Erfurt, Thuringen, remarks:

It is true that one...cult title...of Mithras was, or came to be, Deus Sol Invictus Mithras (but he could also be called... Deus Invictus Sol Mithras, Sol Invictus Mithras......Strabo, 15.3.13 (p. 732C), basing his information on a lost work, either by Posidonius (ca 135-51 BC) or by Apollodorus of Artemita (first decades of 1 cent. BC), states baldly that the Western Parthians "call the sun Mithra." The Roman cult seems to have taken this existing association and developed it in their own special way. (Gordon, "FAQ." (Emph. added.))

"Mithra is who the monuments proclaim him—the Unconquered Sun."

As concerns Mithra's identity, Mithraic scholar Dr. Roger Beck says:

Mithras...is the prime traveller, the principal actor...on the celestial stage which the tauctony [bull-slaying] defines.... He is who the monuments proclaim him—the Unconquered Sun. (Beck (2004), 274)

In an early image, Mithra is depicted as a sun disc in a chariot drawn by white horses, another solar motif that made it into the Jesus myth, in which Christ is to return on a white horse. (Rev 6:2; 19:11)

Mithra in the Roman Empire

Subsequent to the military campaign of Alexander the Great in the fourth century BCE, Mithra became the "favorite deity" of Asia Minor. Christian writers Dr. Samuel Jackson and George W. Gilmore, editors of The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge (VII, 420), remark:

It was probably at this period, 250-100 b.c., that the Mithraic system of ritual and doctrine took the form which it afterward retained. Here it came into contact with the mysteries, of which there were many varieties, among which the most notable were those of Cybele.

According to the Roman historian Plutarch (c. 46-120 AD/CE), Mithraism began to be absorbed by the Romans during Pompey's military campaign against Cilician pirates around 70 BCE. The religion eventually migrated from Asia Minor through the soldiers, many of whom had been citizens of the region, into Rome and the far reaches of the Empire. Syrian merchants brought Mithraism to the major cities, such as Alexandria, Rome and Carthage, while captives carried it to the countryside. By the third century AD/CE Mithraism and its mysteries permeated the Roman Empire and extended from India to Scotland, with abundant monuments in numerous countries amounting to over 420 Mithraic sites so far discovered.

"By the third century AD/CE Mithraism and its mysteries permeated the Roman Empire and extended from India to Scotland."

From a number of discoveries, including pottery, inscriptions and temples, we know that Roman Mithraism gained a significant boost and much of its shape between 80 and 120 AD/CE, when the first artifacts of this particular cultus begin to be found at Rome. It reached a peak during the second and third centuries, before largely expiring at the end of the fourth/beginning of fifth centuries. Among its members during this period were emperors, politicians and businessmen. Indeed, before its usurpation by Christianity Mithraism enjoyed the patronage of some of the most important individuals in the Roman Empire. In the fifth century, the emperor Julian, having rejected his birth-religion of Christianity, adopted Mithraism and "introduced the practise of the worship at Constantinople." (Schaff-Herzog, VII, 423)

From a number of discoveries, including pottery, inscriptions and temples, we know that Roman Mithraism gained a significant boost and much of its shape between 80 and 120 AD/CE, when the first artifacts of this particular cultus begin to be found at Rome. It reached a peak during the second and third centuries, before largely expiring at the end of the fourth/beginning of fifth centuries. Among its members during this period were emperors, politicians and businessmen. Indeed, before its usurpation by Christianity Mithraism enjoyed the patronage of some of the most important individuals in the Roman Empire. In the fifth century, the emperor Julian, having rejected his birth-religion of Christianity, adopted Mithraism and "introduced the practise of the worship at Constantinople." (Schaff-Herzog, VII, 423)

Modern scholarship has gone back and forth as to how much of the original Indo-Persian Mitra-Mithra cultus affected Roman Mithraism, which demonstrates a distinct development but which nonetheless follows a pattern of this earlier solar mythos and ritual. The theory of "continuity" from the Iranian to Roman Mithraism developed famously by scholar Dr. Franz Cumont in the 20th century has been largely rejected by many scholars. Yet, Plutarch himself (Life of Pompey, 24) related that followers of Mithras "continue to the present time" the "secret rites" of the Cilician pirates, "having been first instituted by them." So too does the ancient writer Porphyry (234-c. 305 AD/CE) state that the Roman Mithraists themselves believed their religion had been founded by the Persian savior Zoroaster.

In discussing what may have been recounted by ancient writers asserted to have written many volumes about Mithraism, such as Eubulus of Palestine and "a certain Pallas," Dr. Beck remarks: "Certainly Zoroaster would have figured largely; and so would the Persians and the magi." It seems that the ancients themselves did not divorce the eastern roots of Mithraism, as exemplified also by the remarks of Dio Cassius, who related that in 66 AD/CE the king of Armenia, Tiridates, visited Rome. Cassius states that the dignitary worshipped Mithra; yet, he does not indicate any distinction between the Armenian's religion and Roman Mithraism.

In discussing what may have been recounted by ancient writers asserted to have written many volumes about Mithraism, such as Eubulus of Palestine and "a certain Pallas," Dr. Beck remarks: "Certainly Zoroaster would have figured largely; and so would the Persians and the magi." It seems that the ancients themselves did not divorce the eastern roots of Mithraism, as exemplified also by the remarks of Dio Cassius, who related that in 66 AD/CE the king of Armenia, Tiridates, visited Rome. Cassius states that the dignitary worshipped Mithra; yet, he does not indicate any distinction between the Armenian's religion and Roman Mithraism.

It is apparent from their testimony that ancient sources perceived Mithraism as having a Persian origin; hence, it would seem that any true picture of the development of Roman Mithraism must include the latter's relationship to the earlier Persian cultus, as well as its Asia Minor and Armenian offshoots. Current scholarship is summarized thus by Dr. Beck (2004; 28):

Since the 1970s, scholars of western Mithraism have generally agreed that Cumont's master narrative of east-west transfer is unsustainable; but...recent trends in the scholarship on Iranian religion, by modifying the picture of that religion prior to the birth of the western mysteries, now render a revised Cumontian scenario of east-west transfer and continuities once again viable.

The Many Faces of Mithra

Mainstream scholarship speaks of at least three Mithras: Mitra, the Vedic god; Mithra, the Persian deity; and Mithras, the Greco-Roman mysteries  icon. However, the Persian Mithra apparently developed differently in various places, such as in Armenia, where there appeared to be emphasis on characteristics not overtly present in Roman Mithraism but found as motifs within Christianity, including the Virgin Mother Goddess. This Armenian Mithraism is evidently a continuity of the Mithraism of Asia Minor and the Near East. This development of gods taking on different forms, shapes, colors, ethnicities and other attributes according to location, era and so on is not only quite common but also the norm. Thus, we have hundreds of gods and goddesses who are in many ways interchangeable but who have adopted various differences based on geographical and environmental factors.

icon. However, the Persian Mithra apparently developed differently in various places, such as in Armenia, where there appeared to be emphasis on characteristics not overtly present in Roman Mithraism but found as motifs within Christianity, including the Virgin Mother Goddess. This Armenian Mithraism is evidently a continuity of the Mithraism of Asia Minor and the Near East. This development of gods taking on different forms, shapes, colors, ethnicities and other attributes according to location, era and so on is not only quite common but also the norm. Thus, we have hundreds of gods and goddesses who are in many ways interchangeable but who have adopted various differences based on geographical and environmental factors.

icon. However, the Persian Mithra apparently developed differently in various places, such as in Armenia, where there appeared to be emphasis on characteristics not overtly present in Roman Mithraism but found as motifs within Christianity, including the Virgin Mother Goddess. This Armenian Mithraism is evidently a continuity of the Mithraism of Asia Minor and the Near East. This development of gods taking on different forms, shapes, colors, ethnicities and other attributes according to location, era and so on is not only quite common but also the norm. Thus, we have hundreds of gods and goddesses who are in many ways interchangeable but who have adopted various differences based on geographical and environmental factors.

icon. However, the Persian Mithra apparently developed differently in various places, such as in Armenia, where there appeared to be emphasis on characteristics not overtly present in Roman Mithraism but found as motifs within Christianity, including the Virgin Mother Goddess. This Armenian Mithraism is evidently a continuity of the Mithraism of Asia Minor and the Near East. This development of gods taking on different forms, shapes, colors, ethnicities and other attributes according to location, era and so on is not only quite common but also the norm. Thus, we have hundreds of gods and goddesses who are in many ways interchangeable but who have adopted various differences based on geographical and environmental factors.Mithra and Christ

Over the centuries—in fact, from the earliest Christian times—Mithraism has been compared to Christianity, revealing numerous similarities between the two faiths' doctrines and traditions, including as concerns stories of its respective godmen. In developing this analysis, it should be kept in mind that elements from Roman, Armenian and Persian Mithraism are utilized, not as a whole ideology but as separate items that may have affected the creation of Christianity, whether directly through the mechanism of Mithraism or through another Pagan source within the Roman Empire and beyond. The evidence points to these motifs and elements being adopted into Christianity not as a whole from one source but singularly from many sources, including Mithraism.

"The evidence points to these motifs and elements being adopted into Christianity..."

Thus, the following list represents not a solidified mythos or narrative of one particular Mithra or form of the god as developed in different cultures and eras but, rather, a combination of them all for ease of reference as to any possible influences upon Christianity under the name of Mitra/Mithra/Mithras.

Mithra has the following in common with the Jesus character:

- Mithra was born on December 25th of the virgin Anahita.

- The babe was wrapped in swaddling clothes, placed in a manger and attended by shepherds.

- He was considered a great traveling teacher and master.

- He had 12 companions or "disciples."

- He performed miracles.

- As the "great bull of the Sun," Mithra sacrificed himself for world peace.

-

He ascended to heaven.

He ascended to heaven. - Mithra was viewed as the Good Shepherd, the "Way, the Truth and the Light," the Redeemer, the Savior, the Messiah.

- Mithra is omniscient, as he "hears all, sees all, knows all: none can deceive him."

- He was identified with both the Lion and the Lamb.

- His sacred day was Sunday, "the Lord's Day," hundreds of years before the appearance of Christ.

- His religion had a eucharist or "Lord's Supper."

- Mithra "sets his marks on the foreheads of his soldiers."

- Mithraism emphasized baptism.

December 25th Birthday

The similarities between Mithraism and Christianity have included their chapels, the term "father" for priest, celibacy and, it is notoriously claimed, the December 25th birthdate. Over the centuries, apologists contending that Mithraism copied Christianity nevertheless have asserted that the December 25th birthdate was taken from Mithraism. As Sir Arthur Weigall says:

December 25th was really the date, not of the birth of Jesus, but of the sun-god Mithra. Horus, son of Isis, however, was in very early times identified with Ra, the Egyptian sun-god, and hence with Mithra...

Mithra's birthday on December 25th has been so widely claimed that the Catholic Encyclopedia ("Mithraism") remarks: "The 25 December was observed as his birthday, the natalis invicti, the rebirth of the winter-sun, unconquered by the rigours of the season."

Yet this contention of Mithra's birthday on December 25th or the winter solstice is disputed because there is no hard archaeological or literary evidence of the Roman Mithras specifically being named as having been born at that time. Says Dr. Alvar:

There is no evidence of any kind, not even a hint, from within the cult that this, or any other winter day, was important in the Mithraic calendar. (Alvar, 410)

In analyzing the evidence, we must keep in mind all the destruction that has taken place over the past 2,000 years-including that of many Mithraic remains and texts—as well as the fact that several of these germane parallels constituted mysteries that may or may not have been recorded in the first place or the meanings of which have been obscured.

The claim about the Roman Mithras's birth on "Christmas" is evidently based on the Calendar of Filocalus or Philocalian Calendar (c. 354 AD/CE), which mentions that December 25th represents the "Birthday of the Unconquered," understood to refer to the sun and taken to indicate Mithras as Sol Invictus. Whether it represents Mithras's birthday specifically or "merely" that of Emperor Aurelian's Sol Invictus, with whom Mithras has been identified, the Calendar also lists the day—the winter solstice birth of the sun—as that of natus Christus in Betleem Iudeae: "Birth of Christ in Bethlehem Judea."